- Last year, China’s economy grew by 6.6%, the slowest annual pace since 1990, and it slowed further to 6.4% in the fourth quarter. Consequently, investors are now focused on whether China’s government can stabilize the economy.

- Expansionary fiscal and monetary policies proved effective during the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) and the 2015 -2016 slowdown. However, they may be less effective today due to secular forces that have reduced China’s growth potential: Its corporate debt burden is approaching unsustainable levels, and credit increasingly is extended to state owned enterprises (SOEs) that are losing money.

- Meanwhile, investors are hoping a resolution to the U.S.-China trade dispute will revive the economy. However, even if a truce materializes, its impact could prove temporary and will not likely reverse China’s secular slowdown.

- The outcome will have an important bearing on the global economy and markets. While the U.S. economy has held up so far, several companies’ fourth-quarter earnings were impacted by tariffs and China’s economy, and the list is likely to grow. If the overall profit outlook is impacted, it will add to market volatility.

Background on China’s Slowdown

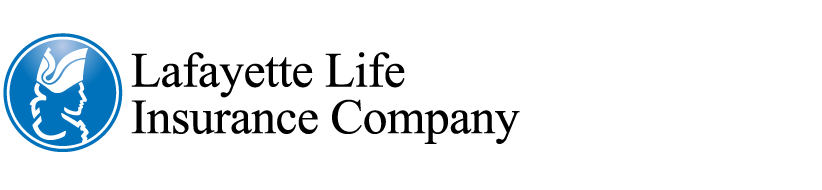

One of the challenges investors confront is to assess whether China’s economic slowdown is primarily cyclical or secular. The economy grew by more than a 10% rate in 2009 in response to massive government stimulus after the 2008 GFC, but it has slowed steadily since then (Figure 1). The 6.6% annual rate in 2018 was the lowest in three decades, and many observers believe the actual growth rate is considerably below what government statistics show.

In dissecting the sources of the recent slowdown, investors need to disentangle the effect of trade tensions with the U.S. and the impact of structural changes inside China. There is general agreement that last year’s slowdown coincided with tariffs being imposed on 10% of Chinese imports to the U.S. during the first half of 2018. When I spoke at a conference in Shanghai in early May, a delegation of U.S. officials were meeting with Chinese counterparts to begin trade negotiations, and it was readily apparent how worried the attendees were about pending tariffs.1

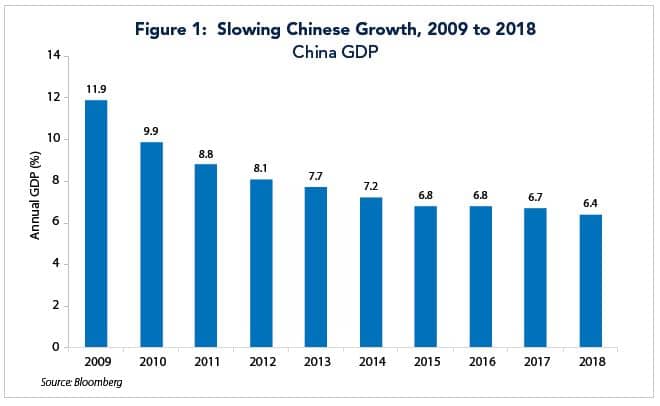

The uncertainty Chinese businesses faced increased in the second half of the year, when the Trump administration threatened to expand the list of tariffs to cover 50% of imports from China. China’s current activity index compiled by Goldman Sachs subsequently plummeted, which sent ripple effects to other parts of the world (Figure 2). There is widespread agreement that a resolution of the trade dispute is critical to stabilize both China’s economy and the global economy. In late November, the U.S. and China agreed to a 90 day truce to see if an agreement could be reached by the beginning of March of this year.

Beyond this, China’s potential growth rate is also decelerating for structural reasons. The country’s economic miracle was founded on agricultural workers in rural areas migrating to urban areas along the coast with higher-productivity manufacturing jobs. But this process has become more challenging as wages in manufacturing have increased and unit labor costs have surged. Such a development is associated with a “middle income trap,” in which countries can grow at very high rates in the early stages of development but growth subsequently plateaus in the middle stages.

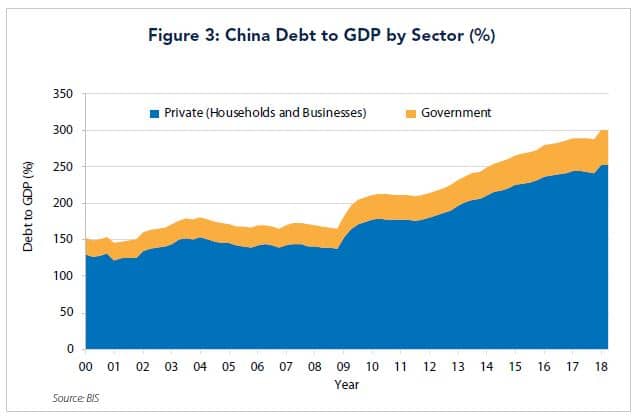

Amid fading productivity growth, the Chinese government has relied increasingly on government stimulus and credit expansion to achieve its growth rate target of 6.0%-6.5%. This has resulted in a doubling of China’s overall debt burden from about 150% of GDP before the GFC in 2008 to 300% currently (Figure 3). The main problem with this strategy is that more and more credit is required to support GDP. For example, the ratio of non-financial credit outstanding to GDP has increased from about 1.5 times at the beginning of this decade to about 5 times currently.2

One reason is that a good part of the recent credit expansion has gone to support SOEs, some of which are firms that the IMF labels as “zombies.” They are firms that do not contribute positive value added, and hence result in even lower productivity growth. Consequently, the Chinese government faces a dilemma of needing to support the economy through debt expansion, at a time when it is becoming less and less effective.

Policy Initiatives

Faced with this predicament, China’s policymakers pursued several measures last year to bolster the economy. They included lowering short term interest rates by more than 200 basis points in two months, allowing the yuan/dollar exchange rate to decline by 10% in six months, while also expanding credit and lowering tax rates. Similar actions were undertaken during China’s slowdown in 2015-2016, which proved effective in bolstering the economy. Accordingly, some are hopeful the same will be true now.

Thus far, the impact of these measures on the economy is not readily apparent. Auto sales, for example, declined in November by nearly 14% over a year ago, and Apple’s recent public filing indicated softness in consumer spending on electronics. China’s imports plummeted in December, and exports also appear headed for a fall based on recent purchasing manager surveys and weakness abroad in Japan, emerging Asia and Europe. One hopeful sign is that housing prices, especially those outside the largest cities, rebounded in December in response to a decline in mortgage rates.

What is clear is China’s policymakers are prepared to take additional actions, as needed, to keep economic growth this year above the official 6% threshold. The central bank, for example, announced a one percent reduction in reserve requirements at the beginning of this year, and additional cuts are contemplated if the economy remains soft. Also, additional fiscal measures are likely despite the country’s mounting debt burden. According to Cornerstone Macro the combined fiscal stimulus from spending increases and tax cuts this year could reach the equivalent of 3% of GDP.3 What is unclear is whether such action will be as effective as in the past.

The Trade Wildcard

The wildcard in the outlook is whether the U.S. and China will be able to reach an agreement by the beginning of March. While both sides wish to do so, the underlying issues are complex and the goals of the Trump administration are unclear. If the disagreement were simply about the size of the bilateral trade imbalance, the issue would be resolved, as China is willing to boost imports from the U.S. and could direct SOEs to do so. The more difficult issues relate to violations of intellectual property and subsidization of businesses by the Chinese government, which the U.S. opposes.

Even if China should acquiesce to U.S. demands, the lingering issue is whether the United States can be assured China will follow through on its pledges. The Chinese government, for example, has floated the notion of “competitive neutrality”, whereby the government would not favor SOEs over private entities.4 However, U.S. officials are skeptical of Beijing’s ability to enforce this policy.

The most likely outcome is a temporary truce will be reached between the two sides, which would bolster world equities for a while. However, because a lasting agreement is harder to achieve, officials may in effect agree to “kick the can down the road.” If so, the impact of a truce on China’s economy and financial markets may prove to be fleeting. The main concern is that the volume of world trade already has begun to slow markedly, and it is a fairly reliable indicator of global growth.

Investment Implications

The outcome will have an important bearing on U.S. and global economies and markets. While the U.S. economy thus far has withstood the impact of a slowdown in China and other regions, several prominent companies including Apple, Microsoft, Caterpillar and Nvidia among others have acknowledged their quarter earnings were impacted by China’s slowdown. Meanwhile, there has been a significant downward revision to earnings expectations for U.S. companies by Wall Street analysts over the past six months. They are now calling for S&P 500 EPS growth of 8.1% in 2019 from more than 20% last year, but Michael Kantrowitz of Cornerstone Macro foresees the possibility they could approach zero by the second half of this year if the global economy stays soft.5

Beyond this, investors must decide whether China’s slowdown can be arrested by policy action or if it is ongoing due to structural changes impacting China’s economy. Our view on this matter is best summed up by Mickey Levy of Berenberg Capital Markets who writes: “Even with stimulus and an agreement on trade, global economies must adjust to the realities of slower China growth in the future.”6 If so, global markets are likely to stay volatile, as we do not believe the full impact of China’s slowdown has been priced into markets.

1 Conference co-sponsored by China Europe International Business School and Darden Business School, Shanghai, May 5, 2018.

2 John Lipsky, “Trade Conflicts and China’s Role in the International Financial System,” presentation for The Chinese University of Hong Kong, January 21, 2019.

3 Nancy Lazar, ”Xi Stands on the Stimulus Pedal. And Will Keep Doing So Until It Works,” Cornerstone Macro, January 24, 2019.

4 Bob Davis, “China’s State Firms Lurk in Trade Talks,” WSJ, January 28, 2019.

5 Michael Kantrowitz, “A Global Earnings Checkup,” Cornerstone Macro, January 28, 2019.

6 Michael Levy, “China’s Economic Slump: Negative Global Ripples,” Berenberg Capital Markets, January 4, 2019.