One of the hallmarks of China’s economic miracle was the willingness of Deng Xiaoping and his successors to allow China’s communist system to evolve into a more market-oriented model in which private businesses coexist alongside state-owned enterprises (SOEs). However, since Xi Jinping became China’s leader in 2012, he has taken steps to reverse the trend. In the process, the role of SOEs has increased while private companies face growing restrictions, especially in the technology arena.

Until recently, global investors seemed oblivious to what was happening. Last November when the Chinese authorities cancelled the IPO for Ant Group that was spun off by Alibaba a decade ago, investors viewed it as a one-off reprimand for Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma. (He had referred to the “pawn shop” mentality of China’s banking system in a public forum.) This was followed by Alibaba being fined a record $2.8 billion for alleged anti-monopoly violations.

This past month, however, foreign investors became concerned by the government’s crackdown on several leading tech companies and companies that raise funds offshore. According to The Wall Street Journal, four leading companies—Alibaba (BABA), Kuaishou Technology, Meituan, Tencent Holdings (TCEHY)—lost about 20% of their market capitalization in July.

The selloff steepened when the government confirmed it would take strong actions to restrain the country’s booming after-school tutoring industry. New rules were announced that would force such companies to be run as not-for-profits, ban them from capital raising and foreign ownership, and forbid teaching during weekends and holidays. The crackdown reportedly occurred because education costs were spiraling and the authorities deemed tutoring to be inequitable.

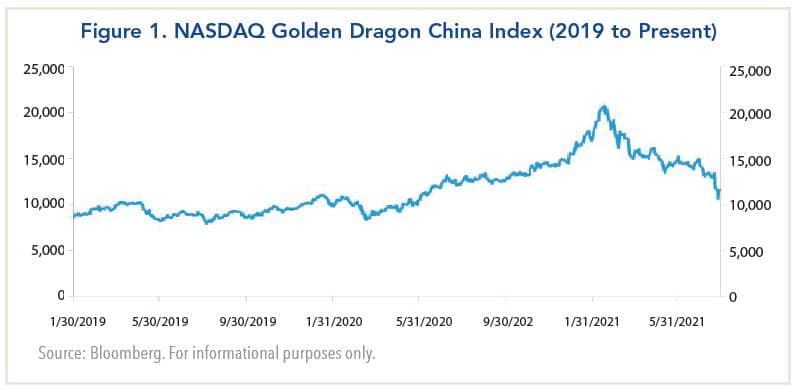

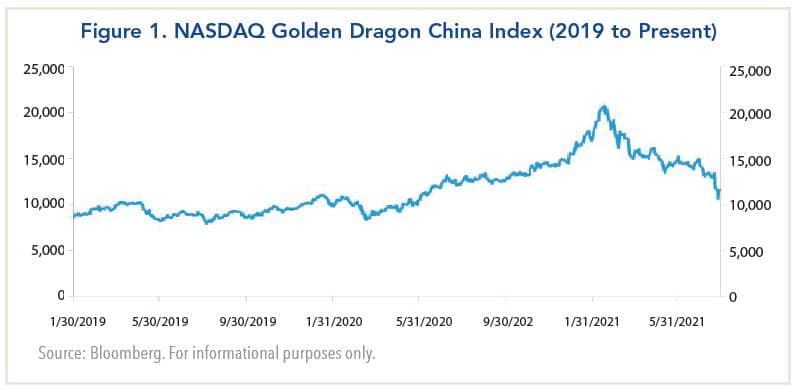

These developments have raised a host of concerns among investors. One is whether similar actions could be taken against private companies in other rapidly growing sectors such as healthcare and property. Another is whether Chinese companies will face restrictions on being listed outside the country, as evinced by a 22% drop in the Nasdaq Golden Dragon China index in July that brought the cumulative decline this year to about 50%.

As a result, investors are wondering why the Chinese government is undermining some of its most successful and productive companies. The official explanations have varied. Shortly after Didi Global Inc. went public in the U.S., The Wall Street Journal reported that Chinese regulatory authorities said they would tighten oversight of overseas-listed companies and they launched a cybersecurity probe into the company. The article quoted a leading securities regulator stating that “financial fraud, insider trading, market manipulations, and other illegal activities of listed companies are increasing.”

The bigger picture is China’s leadership is pursuing the economic strategy that Xi Jinping telegraphed years before. While he began his tenure favoring continuation of the reform process his predecessors pursued, Xi’s policies in fact have increased the role of SOEs. In a book written in 2019, Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute documents how China’s private sector has been significantly diminished over the last decade. At the same time, China’s state sector has grown significantly which has reduced the overall efficiency of China’s economy.

To some extent, the recent clampdown on Chinese entrepreneurs reflects Xi’s view that they should put the nation ahead of their business interests. Jerome Cohen, an expert in Chinese law, reportedly worries that actions against Jack Ma and Sun Dawu, a billionaire who was sentenced to 18 years in prison, could signal a broader campaign to curb the influence of leading entrepreneurs who do not tow the Party’s line.

As this message permeates, some prominent China watchers have taken note and now question whether China’s economic miracle can continue.

In an article for The Atlantic, Michael Schuman, observes that China’s pivot from market-based reforms to increased regulation and reduced overseas reliance may stem from the Trump administration’s restrictions on Huawei Technologies and broad tariff increases on Chinese products. He concludes: “But if Xi succeeds in replacing more of what China purchases from the world, he will also undermine the economic rationale for continued engagement with a brutal authoritarian regime. Xi thinks he is shielding China against isolation. He could instead be causing it.”

A similar sentiment is shared by Steve Roach, a self-proclaimed “congenital optimist” on the Chinese economy in article for Project Syndicate. He observes there is no dearth of explanations for China’s clampdown on businesses with security being the most common. However, he believes it has reached the point where it is undermining the confidence of businesses and consumers alike. He concludes that, “China’s mounting deficit of animal spirits could deal a severe, potentially lethal, blow to my own long-standing optimistic prognosis for the ‘Next China’.”

The bottom line is that many people view China’s actions to take aim on its dynamic technology as being akin to killing the goose that laid the golden eggs. It is the key sector the Chinese government is counting on to lead the economy as it transitions to a higher stage of development. If it were to be held back by regulatory restraint, the risk is that China’s growth trajectory could slow even more than is currently envisioned.

Finally, the impact that regulatory changes are having on businesses and share prices is causing foreign investors to reassess whether China is investable. A recent report by J.P. Morgan Private Bank observes that while new regulations have wiped out billions in market capitalization, it concludes that investors can still navigate Chinese assets. However, the report also states that investors must realize that, “At the moment, China seems more focused on establishing what it deems to be sound financial and social policies domestically rather than catering to foreign investors.”

My own take is that investing in China was always challenging because of difficulties understanding accounting and political intricacies of conducting business there. Now, the recent plethora of regulatory edicts means investments are also subject to much greater “event risk” that is extremely difficult to assess. In these circumstances, the best advice for individual investors is caveat emptor.

A version of this article was posted to Forbes.com on August 3, 2021.

Until recently, global investors seemed oblivious to what was happening. Last November when the Chinese authorities cancelled the IPO for Ant Group that was spun off by Alibaba a decade ago, investors viewed it as a one-off reprimand for Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma. (He had referred to the “pawn shop” mentality of China’s banking system in a public forum.) This was followed by Alibaba being fined a record $2.8 billion for alleged anti-monopoly violations.

This past month, however, foreign investors became concerned by the government’s crackdown on several leading tech companies and companies that raise funds offshore. According to The Wall Street Journal, four leading companies—Alibaba (BABA), Kuaishou Technology, Meituan, Tencent Holdings (TCEHY)—lost about 20% of their market capitalization in July.

The selloff steepened when the government confirmed it would take strong actions to restrain the country’s booming after-school tutoring industry. New rules were announced that would force such companies to be run as not-for-profits, ban them from capital raising and foreign ownership, and forbid teaching during weekends and holidays. The crackdown reportedly occurred because education costs were spiraling and the authorities deemed tutoring to be inequitable.

These developments have raised a host of concerns among investors. One is whether similar actions could be taken against private companies in other rapidly growing sectors such as healthcare and property. Another is whether Chinese companies will face restrictions on being listed outside the country, as evinced by a 22% drop in the Nasdaq Golden Dragon China index in July that brought the cumulative decline this year to about 50%.

As a result, investors are wondering why the Chinese government is undermining some of its most successful and productive companies. The official explanations have varied. Shortly after Didi Global Inc. went public in the U.S., The Wall Street Journal reported that Chinese regulatory authorities said they would tighten oversight of overseas-listed companies and they launched a cybersecurity probe into the company. The article quoted a leading securities regulator stating that “financial fraud, insider trading, market manipulations, and other illegal activities of listed companies are increasing.”

The bigger picture is China’s leadership is pursuing the economic strategy that Xi Jinping telegraphed years before. While he began his tenure favoring continuation of the reform process his predecessors pursued, Xi’s policies in fact have increased the role of SOEs. In a book written in 2019, Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute documents how China’s private sector has been significantly diminished over the last decade. At the same time, China’s state sector has grown significantly which has reduced the overall efficiency of China’s economy.

To some extent, the recent clampdown on Chinese entrepreneurs reflects Xi’s view that they should put the nation ahead of their business interests. Jerome Cohen, an expert in Chinese law, reportedly worries that actions against Jack Ma and Sun Dawu, a billionaire who was sentenced to 18 years in prison, could signal a broader campaign to curb the influence of leading entrepreneurs who do not tow the Party’s line.

As this message permeates, some prominent China watchers have taken note and now question whether China’s economic miracle can continue.

In an article for The Atlantic, Michael Schuman, observes that China’s pivot from market-based reforms to increased regulation and reduced overseas reliance may stem from the Trump administration’s restrictions on Huawei Technologies and broad tariff increases on Chinese products. He concludes: “But if Xi succeeds in replacing more of what China purchases from the world, he will also undermine the economic rationale for continued engagement with a brutal authoritarian regime. Xi thinks he is shielding China against isolation. He could instead be causing it.”

A similar sentiment is shared by Steve Roach, a self-proclaimed “congenital optimist” on the Chinese economy in article for Project Syndicate. He observes there is no dearth of explanations for China’s clampdown on businesses with security being the most common. However, he believes it has reached the point where it is undermining the confidence of businesses and consumers alike. He concludes that, “China’s mounting deficit of animal spirits could deal a severe, potentially lethal, blow to my own long-standing optimistic prognosis for the ‘Next China’.”

The bottom line is that many people view China’s actions to take aim on its dynamic technology as being akin to killing the goose that laid the golden eggs. It is the key sector the Chinese government is counting on to lead the economy as it transitions to a higher stage of development. If it were to be held back by regulatory restraint, the risk is that China’s growth trajectory could slow even more than is currently envisioned.

Finally, the impact that regulatory changes are having on businesses and share prices is causing foreign investors to reassess whether China is investable. A recent report by J.P. Morgan Private Bank observes that while new regulations have wiped out billions in market capitalization, it concludes that investors can still navigate Chinese assets. However, the report also states that investors must realize that, “At the moment, China seems more focused on establishing what it deems to be sound financial and social policies domestically rather than catering to foreign investors.”

My own take is that investing in China was always challenging because of difficulties understanding accounting and political intricacies of conducting business there. Now, the recent plethora of regulatory edicts means investments are also subject to much greater “event risk” that is extremely difficult to assess. In these circumstances, the best advice for individual investors is caveat emptor.

A version of this article was posted to Forbes.com on August 3, 2021.