- Following a strong start in January, the U.S. stock market experienced its first correction of 10% in more than a year, ending the first quarter down marginally. The reversal reflects uncertainty about inflation and interest rates and worries about escalating trade tensions.

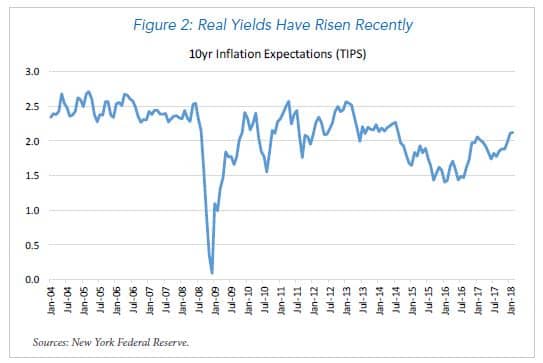

- The rise in bond yields this year is mainly attributable to an increase in real yields, rather than a surge in inflation expectations. The bond market is pricing in two more Fed rate hikes this year, and a fourth one is possible.

- The federal budget outlook has deteriorated, because tax cuts are front-end loaded and the recent spending bill will boost outlays significantly. This raises the specter of further rises in bond yields, as the government competes with the private sector for funding.

- The wild card is trade tensions have increased. This issue is difficult to assess, because President Trump’s negotiating style adds to uncertainty. But there is no mistaking that a trade conflict would be negative for global equities.

- We have not changed our equity positioning, as the usual forces associated with bear markets — namely, inflation, recession, or a credit crunch — are absent. Nonetheless, market volatility is likely to stay elevated.

Surge in Volatility

In the wake of the stock market turmoil in the past two months, many people are wondering what’s wrong. Our answer: Nothing fundamentally with the economy or corporate profits, which continue to perform well. What was unusual was the prolonged period of market calm from the November 2016 election through January of this year, when the stock market rose steadily without a pullback of as much as 3%. Amid this, the U.S. and other advanced equity markets posted returns of 35%, while emerging markets averaged 45%. (Figure 1) These developments heightened the risk of a pullback, which finally occurred in February and March.

Figure 1: Investment Returns for Asset Classes (%)

| Jan. 1, 2016 - Nov. 8, 2016 | jan. 1, 2016 - jan. 31, 2018 | feb. 1, 2018 - mar. 31, 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stock Market | |||

| U.S. (S&P 500) | 6.6 | 35.2 | -6.1 |

| Russell 200 | 6.5 | 33.9 | -2.6 |

| International (EAFE $) | -0.6 | 34.9 | -6.1 |

| Emerging Markets (MSCI $) | 16.5 | 43.2 | -6.4 |

| U.S. Bond Market | |||

| Treasuries | 3.8 | -1.7 | 0.2 |

| IG Credits | 7.8 | 3.1 | -1.2 |

| High Yield | 15.1 | 10.0 | -1.4 |

Source: Bloomberg. For informational purposes only. You cannot invest directly in an index.

The catalyst for the initial correction in February was the January jobs report, which showed average hourly earnings accelerating to 2.9% from 2.5%. This raised concerns that wage and price pressures could be increasing, and it focused investor attention on the possibility that the Fed could raise interest rates more than what was priced into the bond market.

Selling pressures resurfaced in March, this time in response to concerns about escalating tensions between the Trump administration and the principal trading partners of the U.S. The selloff was initiated by the White House’s announcement that the U.S. government would impose duties of 25% and 10%, respectively, on imports of steel and aluminum. It then gained momentum when the administration unveiled tariffs on Chinese imports of up to $60 billion. The stock market subsequently rallied on reports of behind-the-scenes negotiations between U.S. and Chinese officials, but it ended the first quarter marginally below its level at the start of the year.

Amid these developments, market participants are now weighing the following issues: (i) How imminent is the threat of inflation? (ii) How much more are bond yields likely to rise as a result of a strong economy and fiscal stimulus? (iii) What is the risk that trade tensions could escalate and spawn a bear market?

Inflation: Edging Higher, But a Spike Is Unlikely

Some observers are worried that inflation pressures could surface, because the economy is growing by 2.5%-3%, which is above its productive potential, with the unemployment rate hovering just above 4%. In the past, wage pressures would build when the unemployment rate dipped below 5%, but this has not happened in the current expansion. One reason is there is a pool of workers that hold part time jobs who are prepared to work full time as these jobs become available.

In addition, the strengthening of the economy over the past year has been accompanied by an improvement in labor productivity. Consequently, even though wage pressures as measured by average hourly earnings have increased, unit labor costs are relatively unchanged. Therefore, businesses are not compelled to boost prices to offset rising costs.

Nor is there evidence that inflation expectations have increased materially. Rather, most of the recent run-up in bond yields has been associated with a rise in real yields, as reflected in TIPs (Figure 2).

On the policy front, the Federal Reserve under Chair Jerome Powell continued to raise the funds rate gradually at the March FOMC meeting. And the latest Fed forecast suggests it is prepared to accept inflation somewhat above its 2% target. The bond market is pricing in two additional rate hikes this year, which is consistent with expectations of Fed officials. However, bond market participants expect rates to plateau beginning in 2019, whereas Fed officials anticipate further rate increases.

On the policy front, the Federal Reserve under Chair Jerome Powell continued to raise the funds rate gradually at the March FOMC meeting. And the latest Fed forecast suggests it is prepared to accept inflation somewhat above its 2% target. The bond market is pricing in two additional rate hikes this year, which is consistent with expectations of Fed officials. However, bond market participants expect rates to plateau beginning in 2019, whereas Fed officials anticipate further rate increases.

Implications of Lax Fiscal Policy

Even if inflation does not accelerate, one factor that could lead to higher bond yields is a marked deterioration in the outlook for the federal budget deficit. The tax legislation that was enacted in December is expected to add one trillion dollars to the federal deficit over the next ten years, and much of this is front-end loaded into the current year. At the same time, the spending bill that was enacted in late March is expected to add another $400 billion to the deficit in the next two years.

As a result, the budget deficit is now expected to double to 5% of GDP by 2019. This not only is well above what the Congressional Budget Office was projecting, but it could worsen the long-term outlook by $2 trillion if the policies in the budget deal are extended into the future.

The deterioration in the budget deficit has important ramifications for financial markets. First, it will occur at a time when companies are ramping up their capital spending. Although many businesses are currently flush with cash and some are likely to repatriate earnings from abroad, the federal government increasingly will compete with the private sector for funding in the future.

Second, an enlarged budget deficit is likely to result in an increased U.S. trade deficit. The reason: Government spending does little to boost exports, while the tax stimulus contributes to increased imports. This situation is reminiscent of what happened in the Reagan years, when the U.S. ran so-called “twin deficits.” In order to attract the necessary capital inflows from abroad, the U.S. had to maintain high real interest rates. With rates relatively low today, the likelihood is they will have to rise further in the next few years.

Threat of Trade War: Real or Imagined?

The new market development is whether recent trade sanctions by the Trump administration marks the beginning of a trade conflict. While Donald Trump campaigned in 2016 on abrogating NAFTA and imposing across-the-board tariffs on imports from China, trade issues were not a priority following his election.

Trade issues, however, have moved front and center this year. The action to boost tariffs on solar panels and washing machines in January drew little market reaction, but the subsequent announcement about imposing duties on steel and aluminum of 25% and 10%, respectively, caught policymakers in the U.S. and abroad off guard. National security reasons were cited as the justification, giving the President considerable latitude to act. This action was followed by yet another announcement that was directed against China, in which duties are to be raised on imports totaling up to $60 billion. Meanwhile, the U.S. government is investigating alleged violations of intellectual property rights by China.

These developments culminated in a steep stock market decline, as investors worried that trade tensions could escalate and lead to a trade war with China. The stock market subsequently rallied upon reports of behind-the-scenes negotiations between the U.S. and China. However, investors are unsure whether the White House actions are a bargaining ploy to extract concessions from trading partners, or a threat that the Trump administration is prepared to pursue if negotiations fail to deliver the desired outcome.

There is no way of knowing the outcome, as President Trump’s style of negotiating is to begin with bold moves and then to strike deals as he sees fit. One problem with this tactic, however, is markets are likely to react if there is a full blown policy dispute.1 The performance of the U.S. dollar could provide an indication of whether international investors are losing confidence in U.S. policy making. Normally, the dollar would strengthen as interest rate differentials widen in its favor; however, the combination of a weaker dollar and rising U.S. bond yields would signal that international investors are requiring a greater risk premium to hold dollars.

Investment Implications

Amid these developments, we have not altered our equity strategy, which continues to emphasize high-quality names with franchise value. The main reason is that factors normally associated with bear markets – namely, recession, inflation, or a credit crunch – are absent today. That said, we believe volatility will remain elevated, as the stock market is supported by solid earnings growth while the prospect of rising interest rates and trade tensions impact valuations.

In our bond portfolios, we remain comfortable with a modest overweight to credit risk. Economic fundamentals remain solid, but credit spreads, even with recent volatility, remain relatively narrow. In terms of interest rate risk, we are positioning portfolios similar to market benchmarks. Expectations for further Fed tightening are fair given our economic outlook. Inflation data has firmed recently and is generally reflected in future inflation expectations.

1 In 1987, for example, a trade dispute between the U.S. and Japan caused bond yields to spike during the first quarter. It was a prelude to the October 1987 stock market crash, when Japan and Germany clashed with the U.S. over monetary and exchange rate policies.