- The mood at the IMF annual meetings last week was somber, as policymakers lamented the toll the U.S.-China trade war was taking and the prevalence of negative interest rates in Europe and Japan. The IMF’s latest forecast calls for global growth this year to slow to 3%, the weakest since 2009.

- Prospects for 2020 hinge in part on whether the recent lessening of trade tensions will last. Upcoming talks between President Trump and President Xi in mid-November will provide the first indication.

- Some forecasters call for global growth to trough early next year if the truce proves durable. However, we believe uncertainty over trade will linger and Fed easing will have only a limited impact on growth.

- Bond yields are likely to remain low and the stock market’s upside will be limited if the global slowdown persists. A U.S. recession is not our base case, but consumer confidence is key.

Pessimism at the IMF Annual Meeting

Last week I attended an event in Washington, D.C. to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Bretton Woods conference.1 It coincided with the IMF annual meetings, and the speakers included policymakers from Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the United States.

What was striking was a general sense that the global economy and financial system confronted challenges of epic proportions. This is summarized in the introduction to a compendium the sponsors published that cited distortions from expanded central bank balance sheets, large and rising debt burdens, and the prevalence of negative interest rates in Europe and Japan.2 Structural problems related to aging demographics and low productivity growth in developed countries were also discussed.

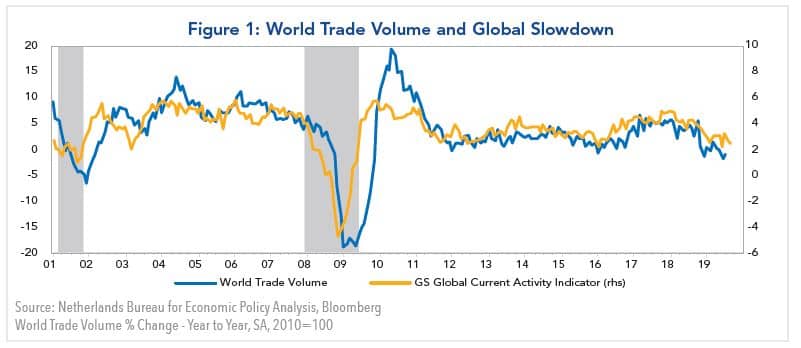

Another challenge has emerged in the form of an escalating trade war between the United States and China. It has taken a toll on world trade and manufacturing (Figure 1) and has resulted in a steady slowdown of the world economy over the past 18 months.

Studies by the Federal Reserve, IMF, and Morgan Stanley estimate that trade tensions and their impact on business confidence and capital spending have cost the global economy on the order of a full percentage point of growth. Global growth has decelerated close to a post-crisis low of 2.9% year-over-year in the third quarter of 2019 from a peak of 4.1% in the first quarter of 2018.3 (Note: The impact on the U.S. economy is not as great because international trade comprises a smaller percentage of U.S. GDP.)

Global Growth Prospects for 2020

Assessments of the outlook for the coming year hinge in part on whether trade tensions will persist or abate. After a protracted period of negotiations, the United States and China made some progress towards reaching a partial agreement this month, although details on the agreement are scant. The main takeaway is the Trump administration held off imposing a 5% surcharge on duties that were scheduled for mid- October in return for a pledge by the Chinese government to increase purchases of U.S. agricultural goods. However, there is a wide discrepancy between the purchases President Trump is seeking – between $40 billion to $50 billion annually – versus what the Chinese government believes is feasible.

Meanwhile, President Trump has indicated he will not sign a formal agreement until he meets with President Xi at the upcoming APEC conference in Chile in mid-November. The meeting could also clarify whether the U.S. government will proceed with plans to impose duties of 15% on imports totaling $157 billion in mid-December. While the majority of goods are consumer items, they will not impact retailers ahead of the Christmas holiday season.

The outcome on trade policy could determine whether the global economy continues to soften or turns the corner. Morgan Stanley’s economists believe the global economy could begin to recover in the first quarter of 2020 if the current truce holds up, whereas they see the global economy staying weak into the first part of next year if the next round of tariff hikes is implemented.

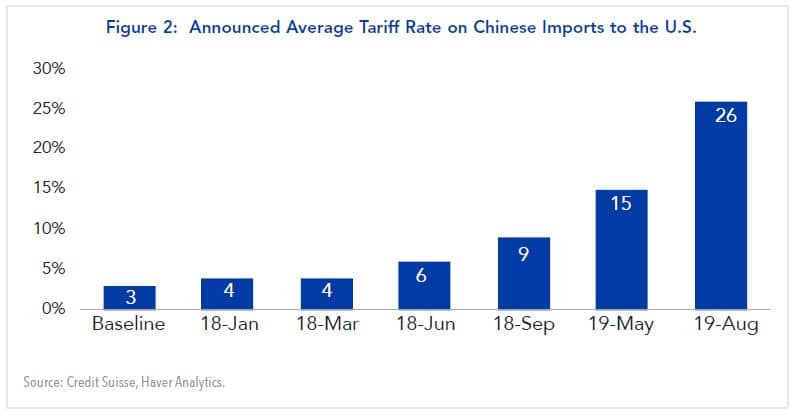

By comparison, economists at UBS are more bearish: They believe the cumulative effect of previous tariff hikes will continue to be felt on the U.S. economy, and a trade deal would have only a modest positive effect.4 This view is buttressed by an analysis of economists at Credit Suisse, which shows the substantial increase in the average tariff rate on Chinese imports since the middle of this year (Figure 2).5

Fed to the Rescue

In the meantime, we expect the Federal Reserve to lower the federal funds rate by 25 basis points to 1.5%-1.75% at the FOMC meeting at the end of this month. This will bring the cumulative lowering of the funds rate this year to 75 basis points. Thereafter, our expectation is the Fed will pause to see what effect the round of policy moves is having on the economy.

In addition to lowering the funds rate, the Federal Reserve recently announced it will purchase an additional $60 billion of short-term Treasuries per month into the first half of next year. The intent is to ensure there is adequate liquidity so that short-term rates do not spike, as they did in September.

The underlying problem was a shortage of liquidity. Fed officials thought the large volume of excess reserves (over what was required) implied the banking system was flush with liquidity. However, because banks want to have a cushion of reserves to handle contingencies, small changes in the quantity of reserves could have a large impact on overnight rates.

These purchases could almost completely reverse the impact of the Fed’s balance sheet shrinkage that began at the end of 2017. While some observers view them as quantitative easing, Fed officials maintain the actions are technical in nature: They are designed to satisfy the demand for excess reserves in the market place so the Fed can maintain the target band for the funds rate. Another difference is that previous Fed actions were designed to lower long-term bond yields and to flatten the yield curve. By comparison, the latest actions could cause the curve to steepen, because purchases are concentrated at the front end of the curve.

Investment Implications

As 2019 winds down, it is clear the U.S.-China confrontation has taken a toll on world trade, and it is likely the principal factor behind the slowdown of global growth over the past 18 months. Consequently, how the trade conflict plays out will have an important bearing on the performance of the global economy in the coming year.

The good news is there has been a cessation in the escalation of trade tensions recently, but it is too early to know whether this is a temporary development or a more fundamental shift in U.S. trade policy. A decision by the Trump administration to refrain from implementing duties scheduled for mid-December would be positive for financial markets. However, the economic impact would be relatively small if existing tariffs are left in place. Accordingly, we do not foresee a quick reversal of the slowdown in the U.S. and global economies.

If the slowdown persists, bond yields are likely to remain close to current levels, and they could drift lower if the Fed were to initiate another round of rate cuts. While this would help support the stock market, we believe the upside is limited by lackluster earnings growth. The main risk to the stock market would be a U.S. recession. This is unlikely as long as consumer spending is solid, but households could feel the impact of the trade war if the Trump administration implements a new round of tariffs in December.

1 The meeting was sponsored by the Center for Financial Stability, an independent, nonpartisan, and nonprofit think tank focused on financial markets for the benefit of investors, officials, and the public.

2 Bretton Woods: The Founders & the Future, edited by Lawrence Goodman and Kurt Schuler, 2019.

3 See Morgan Stanley commentary, “How Big of a Deal?” October 20, 2019.

4 See “U.S. Economic Perspectives,” October 18, 2019.

5 CS House View, “Global Cycle Notes: The most important chart,” October 8, 2019.