The 2020 election will go down as one of the most contentious in U.S. history. It reveals the nation is still deeply divided between voters who are urban vs. rural, coastal vs. heartland, college educated vs. non-college educated, and male vs. female.

Joe Biden is now president-elect, but the election did not produce a “blue wave” sweep of Congress that many anticipated. Republicans maintain control of the Senate by a narrow margin pending two run-off elections in Georgia, and the Democrats’ margin in the House is smaller. In this respect, it is unlikely to be a “game-changer” as the 2016 election was.

Four years ago, my advice for investors was to focus on likely policy changes that would drive the economy and markets. I divided Trump’s policies into three categories in terms of their likely market impact:

- Good – tax cuts and deregulation that would bolster economic growth

- Bad – enlarged budget deficits that would spawn higher interest rates

- Ugly – a looming trade war with China that would add to uncertainty

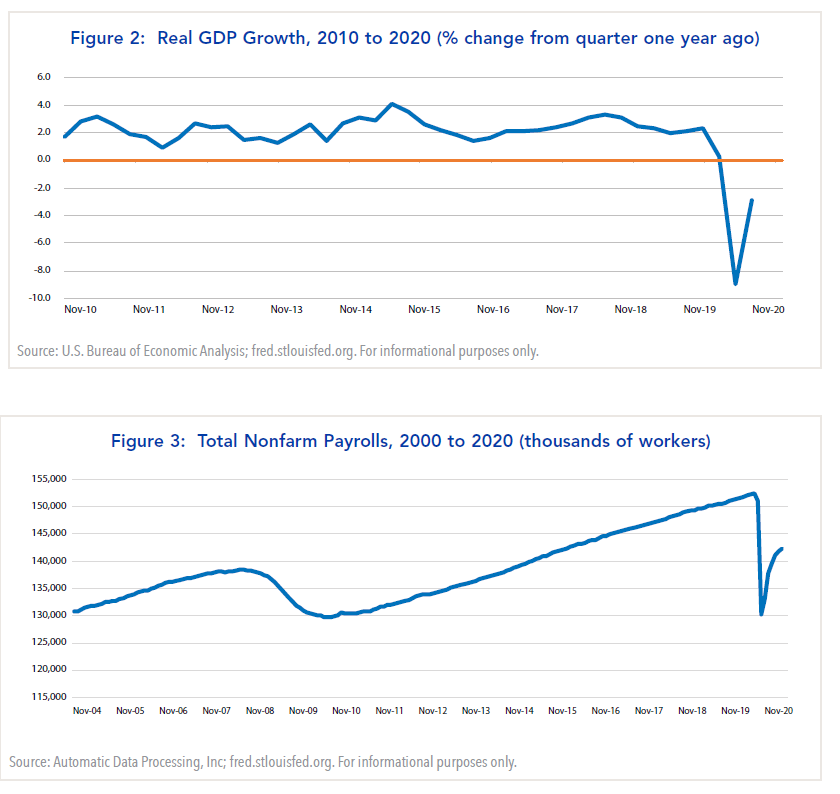

This assessment proved to be valid for tax cuts and the trade war. Trump’s election unleashed “animal spirits” and the U.S. stock market went on a roll until the trade war with China interrupted it in late 2018, and the COVID-19 pandemic hit in the first quarter of this year. Even then, the stock market generated an annualized return over the last four years of 14.3% for the S&P 500 Index and 22.5% for NASDAQ (Figure 1).

| STOCK MARKET | Jan 20, 2009 - jan 19, 2013 | jan 20, 2013 - jan 19, 2017 | nov 8, 2016 - nov 3, 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. (S&P 500) | 19.1 | 13.5 | 14.3 |

| Russell 2000 | 21.5 | 12.3 | 9.3 |

| NASDAQ | 22.9 | 16.8 | 22.5 |

| International (EAFE $) | 14.7 | 4.2 | 6.2 |

| Emerging Markets (MSCI $) | 23.5 | -1.9 | 8.5 |

| U.S. Bond Market | JAN 20, 2009 - JAN 19, 2013 | JAN 20, 2013 - JAN 19, 2017 | NOV 8, 2016 - NOV 3, 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treasuries | 3.4 | 1.1 | 3.7 |

| IG Credit | 10.2 | 2.6 | 5.4 |

| High Yield | 20.8 | 5.2 | 5.7 |

One of the surprises was that bond yields did not rise materially in the first three years of the Trump era, despite a steady rise in the federal budget deficit. Moreover, yields plummeted after the pandemic hit this year.

Looking ahead, the big unknown is whether policies of the Trump era will be reversed, and the extent to which Democrats will have to settle for more limited changes than their agenda calls for.

Assessing Biden’s Fiscal Plan

To help finance increased federal spending, Biden would roll back the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA), the signature legislation of the Trump presidency. Key features of Biden’s plan are the corporate tax rate would be increased to 28% from 21%. On the personal side, households with adjusted gross income (AGI) of $400,000 or less would not see their taxes increase directly. In addition, the marginal tax rate on capital gains and dividends would be nearly doubled from 24% to 43%.

Heading into the elections, Biden’s stance on taxes raised the specter that investors might take capital gains before these policies were enacted. In the wake of the elections, however, many investors now believe the prospect of achieving such broad-based changes is low. The reason: Senate Republicans are likely to block tax hikes and large-scale government spending.

What appears more attainable is an agreement with Congressional Republicans to pass a stimulus bill that will extend key provisions of The CARES Act, although the size and composition are not known yet. Another possible area for compromise is increased spending on infrastructure.

Impact of Outsized Budget Deficits on Bond Yields

Thus far, the bond market is unfazed by this outcome. One reason is the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has expanded from about $4 trillion to more than $7 trillion this year mainly reflecting purchases of government securities. Despite this, inflation has stayed low and the Federal Reserve has altered its strategy to achieve a targeted average annual rate of inflation of 2%. This means it is prepared to allow temporary overshoots above the target. At the September FOMC meeting, the Fed signaled rates could stay near zero for several years.

In these circumstances, increased government spending is unlikely to generate substantially higher Treasury bond yields in the coming year. Yields on 10-year Treasury inflation-indexed bonds have fallen to an all-time low of minus 1%. Thus, with inflation expectations running in the vicinity of 1.7%, the nominal yield on the 10-year Treasury is likely only 0.7%.

The bottom line is that investors should be prepared for Treasury yields to stay unusually low a while longer. However, Treasury yields have risen recently amid hopes that a vaccine to combat COVID-19 could become available, and they could rise further next year if economic growth revives.

How Will U.S. Trade Policy Change?

One of the defining features of the Trump era was a tougher U.S. stance on China and the imposition of substantial duties on imports from China. This represented a fundamental reversal in the traditional Republican stance that favored free trade.

The stated objectives of the tariff hikes – to reverse the decline in U.S. manufacturing and the overall U.S. trade deficit – were not achieved. And contrary to President Trump’s assertions, the costs of the tariffs were largely born by U.S. businesses and consumers rather than Chinese exporters.

Yet, despite this, Joe Biden thus far has not announced any forthcoming changes in trade policy with China. One reason is he wants to restore the traditional support that Democrats had with blue collar workers and to deflect criticism that Democrats are soft on China. For these reasons, investors believe Biden is not in a hurry to scale back the tariff increases that Trump imposed.

However, there is reason to expect that Biden will try to rebuild relations with China so they are less strained. Going forward, he is likely to favor multi-lateral negotiations. The bottom line is U.S. trade policy is likely to be far less confrontational than in the Trump era, which should reduce one source of market risk.

Dealing with COVID-19

Finally, the issue that emerged this past year and which influenced the election was the divergent response to the COVID-19 pandemic by Trump and Biden. When the pandemic hit in the first quarter the consensus among economists was it could be the worst downturn in the post-war era. Fortunately, it also turned out to be one of the shortest recessions. As a result of massive government spending and added monetary support, the economy has experienced an impressive recovery fueled by a rebound in consumer spending and housing.

What is especially telling is how resilient the economy has been thanks in large part due to the digital economy and the adaptability of the workforce. The number of applications for new businesses has spiked this year. Still, while these trends are encouraging, the economy is not fully recovered and the pace has slowed recently.

Looking ahead, the main concern is the incidence of COVID-19 spiking markedly in the U.S. and Europe. While a broad-based shutdown of U.S. businesses is not likely, targeted shutdowns are possible that could slow the recovery. This begs the question: What can the government do that won’t undermine the recovery?

For President Trump, the answer is that the cure cannot be worse than the problem, and he is opposed to shutdowns of businesses while favoring school re-openings. Trump has also supported quick action to develop a vaccine to combat COVID-19, and the recent announcement by Pfizer that a new drug has proved effective in 90% of the cases tested has raised hopes that a cure could be available next year.

Joe Biden, by comparison, believes a sustained economic expansion is contingent on the pandemic being contained through greater involvement by the federal government. One of Biden’s first actions as president-elect was to announce he would form a task force of leading scientists and experts to advise him on how to control the pandemic. Biden’s plan is expected to establish national guidelines to stop outbreaks and to carry out contact tracing, as well as making investments in vaccine distribution.

Investment Implications: Impact of the Election is Limited

Weighing all of these possibilities, what should a prudent investor consider in the aftermath of the elections?

The main conclusion is that investors should not over-react to the election outcome. The reason: Many of Biden’s policy initiatives – especially large-scale government spending and tax hikes – are unlikely to be implemented. The initial market response has been favorable, and investors are hopeful legislation will be enacted to extend key provisions of the CARES Act.

Beyond this, it is too early to know what legislation will be forthcoming and what will be pared down or bypassed. That’s why the outcome to the Congressional elections matters so much, especially the two run-off elections in Georgia for the Senate.

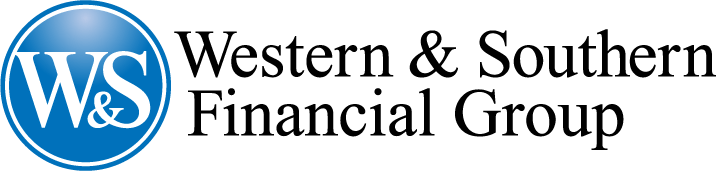

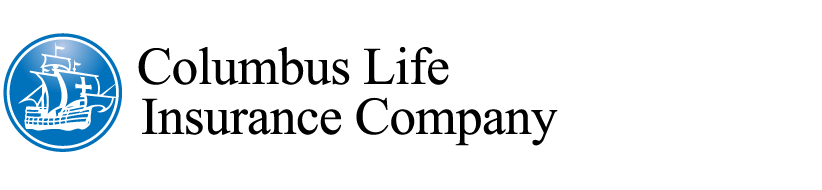

In regards to the long-term outlook, the performance of the economy is what will likely ultimately drive the markets. The main takeaway is that despite all of the political drama over the past four years, it is hard to differentiate the impact of political changes on the economy: Growth of real GDP averaged about 2.5% per annum prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the pace of jobs creation was fairly steady over the past eight years (Figures 2 and 3).

My own take is that the U.S. economy has proved to be highly resilient to shocks in the past two decades, and the prospects for 2021 are generally favorable as the economy continues to recover from the worst pandemic in 100 years. For this reason, we are not altering our investment strategy that maintains a moderate overweight in risk assets.