- At the recent Jackson Hole symposium, the Federal Reserve (Fed) announced a new monetary policy framework that introduced an average inflation targeting regime and broader definition of full employment.

- For inflation, the goal is now to achieve an average inflation target of 2% versus the current annual target of that amount. This means the Fed will now allow inflation to overshoot 2% temporarily if it was below that level previously and vice versa.

- Employment will now be viewed in a broader context that will focus on maximizing employment as long as inflation risks are not evident. This means the Fed will no longer preemptively raise interest rates as the unemployment rate reaches low levels. Instead, it will wait until price pressures emerge.

- The Fed’s main challenge is to demonstrate it can achieve its inflation target after years of undershooting 2%, without stoking fears that it will lose control of the process.

- Markets reacted positively to the announcement, but achieving the new goals will be a long-term effort with many uncertainties. In portfolios, we remain positioned for relatively stable interest rates and a continuation of economic growth supported by fiscal and monetary policy.

A New Way to Target Inflation

In November 2018, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) launched the first ever comprehensive review of its monetary policy framework. The undertaking, focused on the Fed’s strategies, tools, and communications practice, solicited opinions from outside experts and engaged the public in a series of Fed Listens events. Last week, FOMC Chairman Jay Powell summarized the outcome of the review at the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole symposium.

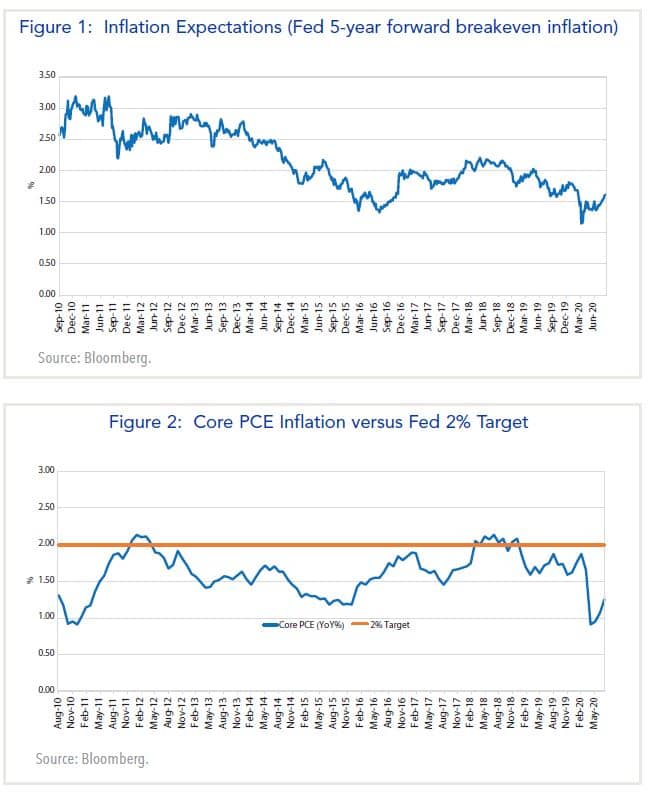

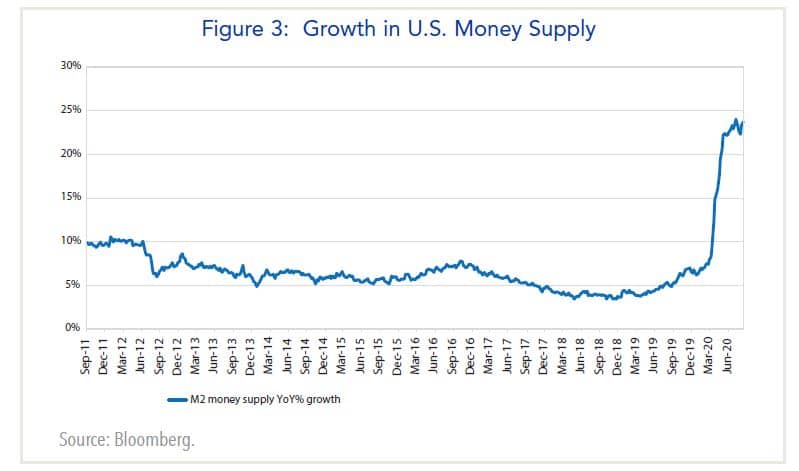

The most important item on the agenda was the FOMC’s inflation-targeting strategy, which has targeted an annual inflation rate of 2% as measured by the price index of the personal consumption (PCE) deflator. While the FOMC’s goal has been to anchor long-term inflation expectations, this metric has only averaged 1.3% per annum in the past eight years. Moreover, with the Fed funds rate now close to zero, policymakers are concerned that falling inflation expectations raise the expected real interest rate, thereby tightening financial conditions.

To address this problem, the FOMC adopted what it refers to as flexible average inflation targeting. In the future, the Fed will aim to achieve average annual inflation of 2% over a prescribed period. In practice, the Fed will now allow inflation to exceed 2% following a period of below target inflation such as the U.S. has experienced for the past several years. This procedure differs from the conventional way of targeting inflation, in which bygones are bygones – i.e., it ignores past misses and begins each year anew.

While the new regime of average annual inflation targeting is clear, market participants are unsure whether it can be attained. Inflation expectations imbedded in markets have persisted at low levels in recent years (Figure 1). With inflation consistently below 2% since the financial crisis (Figure 2), markets doubt the ability and desire of the Fed to achieve target inflation. Additionally, desire alone will not result in achieving this new target. The Fed will likely adopt new measures over the coming months to solidify confidence in the new framework.

The most important item on the agenda was the FOMC’s inflation-targeting strategy, which has targeted an annual inflation rate of 2% as measured by the price index of the personal consumption (PCE) deflator. While the FOMC’s goal has been to anchor long-term inflation expectations, this metric has only averaged 1.3% per annum in the past eight years. Moreover, with the Fed funds rate now close to zero, policymakers are concerned that falling inflation expectations raise the expected real interest rate, thereby tightening financial conditions.

To address this problem, the FOMC adopted what it refers to as flexible average inflation targeting. In the future, the Fed will aim to achieve average annual inflation of 2% over a prescribed period. In practice, the Fed will now allow inflation to exceed 2% following a period of below target inflation such as the U.S. has experienced for the past several years. This procedure differs from the conventional way of targeting inflation, in which bygones are bygones – i.e., it ignores past misses and begins each year anew.

While the new regime of average annual inflation targeting is clear, market participants are unsure whether it can be attained. Inflation expectations imbedded in markets have persisted at low levels in recent years (Figure 1). With inflation consistently below 2% since the financial crisis (Figure 2), markets doubt the ability and desire of the Fed to achieve target inflation. Additionally, desire alone will not result in achieving this new target. The Fed will likely adopt new measures over the coming months to solidify confidence in the new framework.

Employment

The second, less anticipated, result of the framework review was a change to the way the Fed will evaluate the labor market in the context of maximizing employment. In the past, the Fed’s focus was achieving a level of employment that would not generate inflation. If employment rose above this level, the Fed would preemptively tighten policy to ward off expected rises in wages and overall inflation, a relationship described by the Phillips curve.

This supposed linkage between employment and inflation has a poor track record in recent years. Over the last few years, the unemployment rate declined to levels that the Phillips curve would indicate as rising inflation pressures. In contrast, inflation remained subdued and below target.

The weakening in this relationship likely prompted the new focus on maximizing employment until price pressures emerge. The Fed will consider a wide range of indicators when evaluating the labor market, and indicators such as labor force participation will become more important. In the last expansion, a movement of workers back into the labor force resulted in higher labor force participation, more jobs, and higher levels of income. Moreover, this expansion of the labor force can benefit lower income and disadvantaged populations, a step toward narrowing the income gap in the U.S.

From a policy and market perspective, the implications of this change will be most evident when the U.S. returns to a healthy economy with high levels of employment. Provided inflation is consistent with an average of 2%, the Fed should not tighten policy to preempt inflation pressures. Instead, it will likely maintain policies that can foster continued employment growth.

Of these, the first may be the most difficult considering how much time has passed since the Fed achieved its inflation objective. By now, policymakers and economists alike are wondering how well they understand the determinants of inflation: Neither the monetarist framework nor the Phillips curve model has done a good job of predicting inflation over the past two decades.

Several reasons have been put forth including the roles that globalization and rapid technological change have played in contributing to disinflation. Beyond this, inflation expectations have stayed low because of inertia. Thus, the longer inflation is low, the more convinced investors become that it will remain low.

Weighing these considerations, it is not clear the Fed can convince investors inflation will reach 2% any time soon, especially in the context of a soft global economy with high unemployment. Indeed, just because the Fed has altered its strategy does not mean it will succeed.

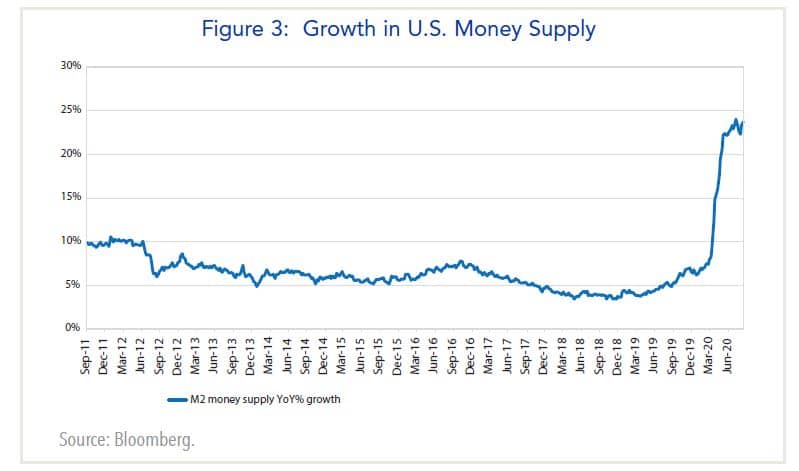

However, this does not mean that inflation will stay subdued indefinitely. The massive expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet and the jump in money supply growth since March has caused some observers to believe that inflation is set to rise sooner than most observers expect (Figure 3).

Yet, there are also reasons to believe the recent acceleration in money is likely to be temporary. Much of it is the result of businesses drawing on pre-existing lines of credit when the coronavirus pandemic hit, as well as households depositing portions of the transfer payments they received from the federal government.

Yet, there are also reasons to believe the recent acceleration in money is likely to be temporary. Much of it is the result of businesses drawing on pre-existing lines of credit when the coronavirus pandemic hit, as well as households depositing portions of the transfer payments they received from the federal government.

The bottom line is that it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when inflation will accelerate, and if it does, how quickly the Fed will react.

This supposed linkage between employment and inflation has a poor track record in recent years. Over the last few years, the unemployment rate declined to levels that the Phillips curve would indicate as rising inflation pressures. In contrast, inflation remained subdued and below target.

The weakening in this relationship likely prompted the new focus on maximizing employment until price pressures emerge. The Fed will consider a wide range of indicators when evaluating the labor market, and indicators such as labor force participation will become more important. In the last expansion, a movement of workers back into the labor force resulted in higher labor force participation, more jobs, and higher levels of income. Moreover, this expansion of the labor force can benefit lower income and disadvantaged populations, a step toward narrowing the income gap in the U.S.

From a policy and market perspective, the implications of this change will be most evident when the U.S. returns to a healthy economy with high levels of employment. Provided inflation is consistent with an average of 2%, the Fed should not tighten policy to preempt inflation pressures. Instead, it will likely maintain policies that can foster continued employment growth.

The Fed’s Challenge: Boosting Inflation Expectations

As the Fed implements its new strategy it confronts two types of challenges. First, can it achieve its stated goal of inflation averaging 2% per annum? Second, once that rate is achieved, can it convince investors it will not tolerate a permanent overshoot?Of these, the first may be the most difficult considering how much time has passed since the Fed achieved its inflation objective. By now, policymakers and economists alike are wondering how well they understand the determinants of inflation: Neither the monetarist framework nor the Phillips curve model has done a good job of predicting inflation over the past two decades.

Several reasons have been put forth including the roles that globalization and rapid technological change have played in contributing to disinflation. Beyond this, inflation expectations have stayed low because of inertia. Thus, the longer inflation is low, the more convinced investors become that it will remain low.

Weighing these considerations, it is not clear the Fed can convince investors inflation will reach 2% any time soon, especially in the context of a soft global economy with high unemployment. Indeed, just because the Fed has altered its strategy does not mean it will succeed.

However, this does not mean that inflation will stay subdued indefinitely. The massive expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet and the jump in money supply growth since March has caused some observers to believe that inflation is set to rise sooner than most observers expect (Figure 3).

Yet, there are also reasons to believe the recent acceleration in money is likely to be temporary. Much of it is the result of businesses drawing on pre-existing lines of credit when the coronavirus pandemic hit, as well as households depositing portions of the transfer payments they received from the federal government.

Yet, there are also reasons to believe the recent acceleration in money is likely to be temporary. Much of it is the result of businesses drawing on pre-existing lines of credit when the coronavirus pandemic hit, as well as households depositing portions of the transfer payments they received from the federal government.The bottom line is that it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when inflation will accelerate, and if it does, how quickly the Fed will react.

Market Implications

The Fed’s new strategy has short- and long-term implications for markets. Over the near term, the new inflation targeting regime will likely require additional steps by the Fed to solidify the commitment to achieving its goals. Having already lowered rates near zero and committed to buy a wide range of assets, next steps will focus on strengthening forward guidance on “lower for longer” interest rates and perhaps changing the pace and/or mix of asset purchases.

In our view, these steps should keep interest rates relatively low, near current levels over the next several months. In addition, these policies will likely continue to support asset markets (e.g. corporate bonds, equities) until the economy can begin healing after the COVID-19 pandemic retreats resulting from a vaccine or reliable treatment.

Over the long term, one of the most positive implications for markets is that the Fed will be less likely to tighten policy too early and economic expansions can continue for longer, a clear positive for asset markets. However, letting the economy “run hot” creates additional risks as the potential for higher inflation and other financial imbalances build. As a result, the exit strategy from the new policy framework increases in difficulty.

Even though many aspects were anticipated by markets, they have reacted positively to the Fed’s announcements. The stock market hit record highs in the days following the announcement. Long-term bond yields rose slightly, but still remain relatively low. The yield curve has steepened as a result of the renewed focus on achieving the inflation target, a trend that we suspect will persist into 2021.

In our view, these steps should keep interest rates relatively low, near current levels over the next several months. In addition, these policies will likely continue to support asset markets (e.g. corporate bonds, equities) until the economy can begin healing after the COVID-19 pandemic retreats resulting from a vaccine or reliable treatment.

Over the long term, one of the most positive implications for markets is that the Fed will be less likely to tighten policy too early and economic expansions can continue for longer, a clear positive for asset markets. However, letting the economy “run hot” creates additional risks as the potential for higher inflation and other financial imbalances build. As a result, the exit strategy from the new policy framework increases in difficulty.

Even though many aspects were anticipated by markets, they have reacted positively to the Fed’s announcements. The stock market hit record highs in the days following the announcement. Long-term bond yields rose slightly, but still remain relatively low. The yield curve has steepened as a result of the renewed focus on achieving the inflation target, a trend that we suspect will persist into 2021.

Positioning Portfolios

In our portfolios, we remain allocated toward risk assets. The fundamental backdrop is improving in spite of uncertainties related to the pandemic and upcoming elections in the U.S. Coupled with persistent policy support, we believe the environment will continue to support these assets.

In balanced portfolios, we are slightly overweight equities relative to fixed income. Within bond portfolios, we are favoring credit sectors (investment grade, high yield, emerging markets) over Treasuries. In terms of interest rates, Fed policy and low inflation should keep interest rates relatively low and we are positioning portfolios close to the benchmark.

In all cap equity portfolios, we are positioned in larger cap, higher return on capital businesses. We have been deploying capital at a measured pace in attractive business models that have become buyable in the wake of the pandemic. Some of these opportunities are lower in market cap and the common theme is the market pricing in around pandemic level returns on capital well into the future.

In balanced portfolios, we are slightly overweight equities relative to fixed income. Within bond portfolios, we are favoring credit sectors (investment grade, high yield, emerging markets) over Treasuries. In terms of interest rates, Fed policy and low inflation should keep interest rates relatively low and we are positioning portfolios close to the benchmark.

In all cap equity portfolios, we are positioned in larger cap, higher return on capital businesses. We have been deploying capital at a measured pace in attractive business models that have become buyable in the wake of the pandemic. Some of these opportunities are lower in market cap and the common theme is the market pricing in around pandemic level returns on capital well into the future.