- During the election campaign, Donald Trump ran for office on restoring lost jobs in manufacturing by renegotiating trade deals and imposing tariffs on imports from countries that are deemed to hurt American workers. Now that he is President, market participants are focusing on what he will do.

- One of his first decisions will be his stance on a “border adjustment tax” (BAT), a key provision in the House Republican tax bill that is intended to incent U.S. companies to produce at home rather than abroad. In an interview last week, Mr. Trump indicated he favors a simpler approach of imposing stiff duties on countries that disadvantage U.S. workers and U.S. based companies that shift production abroad.

- A key problem with the President’s trade policy, however, is that it runs counter to market forces. Because the dollar’s value is mainly driven by capital flows, stronger growth, and rising U.S. interest rates threaten to propel it higher. Also, the President’s fiscal stance of lowering tax rates but not broadening the tax base would likely balloon both the budget and trade deficits.

- The bottom line: President Trump’s efforts to reduce the trade deficit and restore lost jobs in manufacturing are likely to fail. Moreover, his policy of raising tariffs is bound to invite retaliation in which all parties would lose.

President Trump’s Views on Trade & the Dollar

Throughout the Presidential campaign, Donald Trump articulated a stance on international trade that reflects his long-standing views. At the core, his world view is mercantilist: International trade is a zero sum game with winners and losers, and the losers are countries that run trade deficits.

While Mr. Trump’s views on trade are at odds with the post-war order, in which free trade was seen as a means for promoting world growth, he was by no means the only candidate to abandon free trade principles. Indeed, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, for the first time in modern history no presidential candidate ran on a pro free-trade platform. Where Mr. Trump stood apart from other candidates was his call to renegotiate existing trade arrangements and his threats to impose heavy duties on countries and U.S. businesses that are deemed to pursue policies that harm U.S. workers.

Now that he is president, Mr. Trump has announced the United States will withdraw the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific partnership, and he is planning to meet with the leaders from Mexico and Canada to discuss NAFTA. One of the first legislative decisions Mr. Trump will make is his stance on the issue of a border adjustment tax (BAT), which is a key provision in the House Republican tax bill. The BAT is called a “destination based cash flow tax” because it does not include export revenues in corporate taxes, while it excludes imported items from costs. The Republican leaders in the House favor the idea because: (i) it incents businesses to produce at home rather than abroad; and (ii) it is estimated to raise $1 billion in tax revenues over a decade that would help fund the proposed cut in the corporate tax rate to 20% from 35%.

The BAT concept is very controversial because it is untested and critics contend it could be disruptive to businesses with global supply chains. Proponents contend this is not the case because they claim there would be offsetting movements in the dollar. For example, if U.S. exporters were able to reduce the price of a product sold abroad, it would increase demand for dollars and boost the value of the dollar. Accordingly, some economists estimate that if the corporate tax rate were lowered to 20% the dollar would likely appreciate by about that amount, although that issue is subject to debate.

In a recent Wall Street Journal interview, Mr. Trump stated the BAT proposal was too complex, and he favors a simpler approach of raising tariffs on imported goods including those from overseas’ operations of U.S. based companies. He also expressed concern that the dollar was “too strong” in part because China holds down its currency, the yuan: "The yuan is ‘dropping like a rock,’ Mr. Trump said, dismissing recent Chinese actions to support it as being done simply ‘because they don’t want us to get angry.'"

It remains to be seen what the final legislative outcome will be. Some commentators believe the House Republican leaders will continue to press for a BAT; however, to gain the President’s approval, they will have to compromise on provisions of the pending tax bill. As discussed below, the House Republican tax bill is intended to be revenue-neutral, whereas the proposal that Mr. Trump favors would increase the budget deficit significantly.

An Inconsistent Trade Policy: Lessons From the 1980s

Whatever the outcome, President Trump’s approach to trade and the dollar is flawed, in my opinion, because it ignores the impact of market forces on the dollar and the trade balance. In this regard, there are several valuable lessons from the experience of the Reagan presidency in the 1980s that apply today.

One of the main lessons is that the dollar’s value is determined primarily by international capital flows, rather than international trade flows. During the Reagan era, for example, the combination of a resurgent U.S. economy and high U.S. interest rates relative to those abroad attracted massive capital inflows that sent both the dollar and the U.S. trade deficit to then record levels.

U.S. interest rates today, of course, are considerably lower than in the 1980s; nonetheless, they are still well above those abroad. The dollar currently is at a 14-year high on a trade-weighted basis, and it has surged since the presidential election. Should the U.S. economy accelerate, as President Trump is seeking, the Fed is likely to tighten monetary policy further, which would drive the dollar even higher. Similarly, if China continues to experience capital flight, the Chinese yuan is likely to depreciate further, despite efforts of the authorities to limit the decline.

A second lesson is the trade imbalance is likely to widen considerably if the budget deficit increases materially, as was the case in the 1980s, when the U.S. ran “twin deficits” (refer to chart below). The intuition is that increased government spending on the military and infrastructure is likely to boost imports but do little to increase exports. More fundamentally, the national income identity holds where the imbalance on trade is equal to the sum of the budget imbalance and the saving-investment imbalance in the private sector. If the latter is unchanged, the trade deficit increases directly with the change in the budget deficit.

U.S. Budget & Trade Imbalances as a Percent of GDP

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Dept. of Commerce.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Dept. of Commerce.

In this regard, a lot hinges on the type of tax legislation that is forthcoming. Specifically, there is an important difference between the House Republican tax bill, which is designed to be deficit-neutral, with the plan that Mr. Trump campaigned on, which independent research institutions estimate would add about $6 trillion to federal debt outstanding over the next ten years. The primary reasons are the Trump plan calls for deeper cuts in the corporate tax rate to 15% versus 20% in the pending House bill, and the Trump plan does not seek to broaden the tax base, whereas the House bill does.

The bottom line, therefore, is that if President Trump’s efforts to boost economic growth via tax cuts and increased government spending unfold, the trade deficit is likely to expand considerably.

The Worst Outcome: A Needless Trade War

While President Trump’s trade policies are unlikely to produce the results he is seeking, the worst outcome for financial markets would arise if the policies culminated in an unnecessary trade war with China, Mexico, and other countries.

It is hard to tell at this juncture whether President Trump’s call for duties in the neighborhood of 35% on imported items from certain countries is a negotiating ploy to extract a better deal, or whether he is serious and will follow through. Based on his selection of Cabinet appointees to handle trade matters, however, this threat should not be taken lightly. They include Peter Navarro, a China critic to head the new National Trade Council, Wilbur Ross as Secretary of Commerce, and Robert Lighthizer, a lawyer who represents industries seeking government protection via trade barriers. At the same time, President Trump appears determined to declare China a currency manipulator, even though the Chinese Government has spent one trillion dollars in foreign exchange reserves in an attempt to limit the yuan’s depreciation against the dollar.

Should the Administration pursue such a course of action, it would inevitably invite retaliation, either in terms of reciprocal duties on goods from the U.S. and/or diminished purchases of U.S. treasuries. One may wonder why the U.S. would run this risk when unemployment is below 5% and overseas economies are fragile. And while financial markets have shrugged off the possibility thus far, global investors are likely to turn wary if a trade war were to materialize.

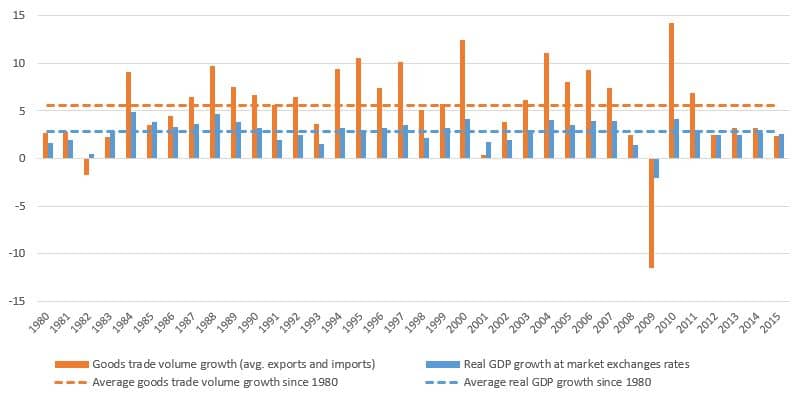

One of the most disturbing aspects of all this is how world leaders today have lost sight of the benefits that free trade has conveyed on the U.S. and global economy during the post-war era. From the early 1980s, when globalization took off, until the mid-2000s, there was a fairly steady expansion of both world trade and economic growth, with world trade expanding at roughly twice the pace of global GDP growth, and free trade policies played a critical role (see chart below). However, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, both global growth and the volume of world trade slowed markedly. This development, in turn gave rise to populism around the world, which threatens to bring increased protectionism that could undermine what was achieved during the post-war order.

Growth in Volume of World Goods Trade & Real GDP, 1980-2015

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2016