- The tariff hikes announced this month is the third round of the trade war that began last year. Unlike two prior episodes, equity market volatility remains relatively low, because the global economy is in better shape today (Figure 1).

- Estimates of the direct impact of the tariff hikes on the U.S. economy are modest — between 0.1%- 0.2% of GDP. However, the toll varies across sectors, and the ultimate impact hinges on how businesses and consumers respond.

- Investors need to consider whether the tariff increases are likely to be permanent. The U.S. now has the highest average tariff rate among leading industrial countries, and it is higher than most emerging markets. Furthermore, national security considerations increasingly are being used to justify trade sanctions.

- We are not altering our investment strategy, because the risk of a U.S. recession is low and profits have held up better-than-expected. However, we are monitoring whether the global economy will soften.

Background

When the U.S. government launched a trade offensive against China in the spring of 2018, I offered the following assessment about the conflict at a conference in Shanghai:

- It would take a long time to play out, because the issues are complex and not easy to resolve.

- It would lead to increased equity market volatility after a strong run from the U.S. elections in November 2016 through January 2018.

- The final outcome was highly uncertain, because the end-goals of the Trump administration were not clear.

Today, one year later, I still cling to these views. Like most investors, I believed a temporary truce would be reached this spring amid indications a deal was close to being completed. Instead, President Trump surprised investors when he announced tariffs on $250 billion of goods imported from China would be raised from 10% to 25%, and they could ultimately be applied to all imports if China did not comply with U.S. demands.

The stated reason was that China’s negotiators had rescinded some of their prior concessions. China’s response was that the terms the U.S. was proposing were unacceptable, because the U.S. intended to keep existing tariffs in place even after a deal was consummated. China, in turn, responded by increasing duties on $60 billion of goods it imports from the U.S.

While global equity markets sold off on the news, they have stabilized since then. One reason is investors are hopeful a deal can be reached after President Trump and President Xi meet at the G-20 summit on June 28-29. The logic is that a trade war would hurt both sides, and neither side wants such an outcome.

My own take is investors are underestimating the challenges of reaching a viable agreement. After a year of negotiations, there are still fundamental disagreements about actions China should take to: (i) reduce the bilateral trade imbalance, (ii) address violations of U.S. intellectual property and (iii) lessen subsidization of state owned enterprises (SOEs) by the Chinese government. Moreover, national security considerations are becoming more important to the U.S.

Meanwhile, President Trump is in no hurry to make concessions, because he believes the U.S. economy is in better shape than China’s. At the same time, President Xi does not want to be perceived as caving into U.S. demands; nor does he face the prospect of elections that President Trump does. Accordingly, the negotiations could drag on into 2020.

The stated reason was that China’s negotiators had rescinded some of their prior concessions. China’s response was that the terms the U.S. was proposing were unacceptable, because the U.S. intended to keep existing tariffs in place even after a deal was consummated. China, in turn, responded by increasing duties on $60 billion of goods it imports from the U.S.

While global equity markets sold off on the news, they have stabilized since then. One reason is investors are hopeful a deal can be reached after President Trump and President Xi meet at the G-20 summit on June 28-29. The logic is that a trade war would hurt both sides, and neither side wants such an outcome.

My own take is investors are underestimating the challenges of reaching a viable agreement. After a year of negotiations, there are still fundamental disagreements about actions China should take to: (i) reduce the bilateral trade imbalance, (ii) address violations of U.S. intellectual property and (iii) lessen subsidization of state owned enterprises (SOEs) by the Chinese government. Moreover, national security considerations are becoming more important to the U.S.

Meanwhile, President Trump is in no hurry to make concessions, because he believes the U.S. economy is in better shape than China’s. At the same time, President Xi does not want to be perceived as caving into U.S. demands; nor does he face the prospect of elections that President Trump does. Accordingly, the negotiations could drag on into 2020.

Impact of Higher Tariffs on the U.S. Economy

The main reason why markets have reacted more calmly to the latest escalation in the trade war is the global economy is in better shape than it was late last year. Investors worried then that China’s economy was vulnerable to a slump in exports to the U.S., and they feared it would spill over to economies that were dependent on China, including those in the European Union and Asia. Also, the U.S. economy softened in the fourth quarter, after experiencing strong growth in the two prior quarters.

These fears have lessened since then, as both the Chinese and EU economies have stabilized. U.S. growth in the first quarter also was stronger-than-expected, and the Fed has signaled it will pause in tightening monetary policy for the foreseeable future.

Investors must now assess whether the escalation in the conflict will take a toll on the U.S. and global economy. In this regard, the U.S. domestic economy is somewhat insulated from trade, with exports accounting for 12% of GDP compared to nearly 47% for Germany, and 18% each for China and Japan. Thus, China and the EU are likely to feel the fallout to a greater extent than the U.S. Estimates of the direct impact of the tariff hikes on the U.S. economy are low – in the vicinity of 0.1%-0.2% of GDP.

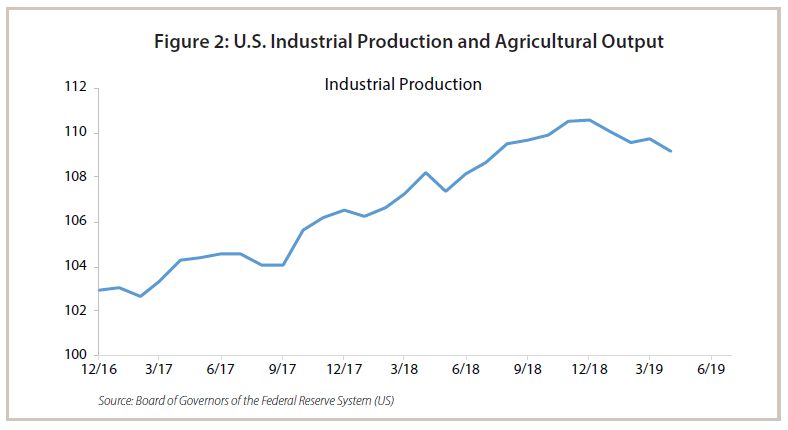

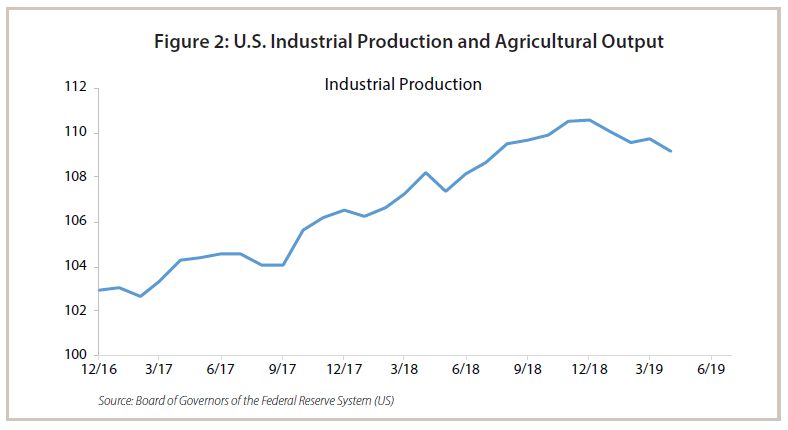

These estimates should be regarded as a lower boundary; however, because global trade ties are complex, and the effect of tariffs varies considerably across companies, sectors and markets. Over the past year, for example, the impact has mainly been felt by the agricultural and manufacturing sectors of the U.S. economy (Figure 2).

Looking ahead, the toll is likely to increase over time, as uncertainty over trade causes businesses to slow their capital investments. According to the Wall Street Journal (May 19), capital spending of S&P 500 companies that have disclosed figures in their quarterly regulatory filings slowed to 3% over a year ago, down from a 20% increase in the first quarter of 2018. This slowdown is attributable to increased uncertainty about trade and the global economy, as well as the fading effect of the federal tax cuts enacted at the end of 2017. Executives at several companies in the survey indicated that lingering trade tensions with China were making them and their customers cautious about the future.

Looking ahead, the toll is likely to increase over time, as uncertainty over trade causes businesses to slow their capital investments. According to the Wall Street Journal (May 19), capital spending of S&P 500 companies that have disclosed figures in their quarterly regulatory filings slowed to 3% over a year ago, down from a 20% increase in the first quarter of 2018. This slowdown is attributable to increased uncertainty about trade and the global economy, as well as the fading effect of the federal tax cuts enacted at the end of 2017. Executives at several companies in the survey indicated that lingering trade tensions with China were making them and their customers cautious about the future.

These fears have lessened since then, as both the Chinese and EU economies have stabilized. U.S. growth in the first quarter also was stronger-than-expected, and the Fed has signaled it will pause in tightening monetary policy for the foreseeable future.

Investors must now assess whether the escalation in the conflict will take a toll on the U.S. and global economy. In this regard, the U.S. domestic economy is somewhat insulated from trade, with exports accounting for 12% of GDP compared to nearly 47% for Germany, and 18% each for China and Japan. Thus, China and the EU are likely to feel the fallout to a greater extent than the U.S. Estimates of the direct impact of the tariff hikes on the U.S. economy are low – in the vicinity of 0.1%-0.2% of GDP.

These estimates should be regarded as a lower boundary; however, because global trade ties are complex, and the effect of tariffs varies considerably across companies, sectors and markets. Over the past year, for example, the impact has mainly been felt by the agricultural and manufacturing sectors of the U.S. economy (Figure 2).

Looking ahead, the toll is likely to increase over time, as uncertainty over trade causes businesses to slow their capital investments. According to the Wall Street Journal (May 19), capital spending of S&P 500 companies that have disclosed figures in their quarterly regulatory filings slowed to 3% over a year ago, down from a 20% increase in the first quarter of 2018. This slowdown is attributable to increased uncertainty about trade and the global economy, as well as the fading effect of the federal tax cuts enacted at the end of 2017. Executives at several companies in the survey indicated that lingering trade tensions with China were making them and their customers cautious about the future.

Looking ahead, the toll is likely to increase over time, as uncertainty over trade causes businesses to slow their capital investments. According to the Wall Street Journal (May 19), capital spending of S&P 500 companies that have disclosed figures in their quarterly regulatory filings slowed to 3% over a year ago, down from a 20% increase in the first quarter of 2018. This slowdown is attributable to increased uncertainty about trade and the global economy, as well as the fading effect of the federal tax cuts enacted at the end of 2017. Executives at several companies in the survey indicated that lingering trade tensions with China were making them and their customers cautious about the future.Will Higher Tariffs Become Permanent?

When President Trump began to increase tariffs in 2018, they were initially seen as a way to extract concessions from trading partners that included Canada, Mexico, the European Union, Japan, as well as China. However, some observers are now questioning whether increased tariffs are becoming a permanent fixture of the U.S. economy.

A recent New York Times article, for example, cites Torsten Slok, Chief Economist of Deutsche Bank Securities, who points out that the average tariff rate in the U.S. has risen to 4.2 percent.1 This rate is the highest of any of the Group of Seven (G-7) industrialized nations, and it is also higher than most emerging markets including Russia, Turkey and China. The Times article goes on to quote Douglas Irwin, a trade historian at Dartmouth College. He observes that what is occurring is a big historic shift in U.S. trade policy:

A recent New York Times article, for example, cites Torsten Slok, Chief Economist of Deutsche Bank Securities, who points out that the average tariff rate in the U.S. has risen to 4.2 percent.1 This rate is the highest of any of the Group of Seven (G-7) industrialized nations, and it is also higher than most emerging markets including Russia, Turkey and China. The Times article goes on to quote Douglas Irwin, a trade historian at Dartmouth College. He observes that what is occurring is a big historic shift in U.S. trade policy:

We've moved away from tariffs as a bargaining chip to get a better deal to tariffs as a means to an end to decouple the economies.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and Larry Kudlow, Director of the National Economic Council, contend that the U.S. actions are intended to support “free and fair reciprocal trade”. However, Trump has been outspoken about the need for increased tariffs to rein in large U.S. trade deficits dating back to the 1980s, when the U.S. ran large trade deficits with Japan.

While both political parties today favor tough measures against China, the Trump administration has been criticized for imposing duties on allies of the U.S. and for using national security as the justification. During the past week, however, there are indications the administration is reining in commercial conflicts across the world in order to focus more exclusively on the conflict with China: It announced it was rescinding tariffs on aluminum and steel that had been imposed on Canada and Mexico. It also postponed a decision to raise duties on autos from the European Union by six months.

Meanwhile, the administration raised the ante on China last week by issuing an executive order that restricts all U.S. technology sales to Huawei, a Chinese telecommunications powerhouse. It also banned Huawei’s equipment from U.S. telecom networks and information infrastructure. As the world’s second largest smartphone maker, Huawei faces the prospect of being locked out of Google Android’s operating system after a three month reprieve expires.

While Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross stated that the sanctions are not part of the trade negotiation, they reflect the administration’s concerns about the security threat China’s technology poses. According to the Financial Times (May 21, 2019), the Huawei sanctions is a “pivotal moment for the global technology industry” that can be seen as the beginnings of a “digital Iron Curtain.”

The bottom line is that just weeks after the markets were expecting a trade truce to be reached between the U.S. and China, the gulf between the two sides is as wide as it has ever been. Moreover, U.S. trade policy has shifted from using countervailing duties to justify trade sanctions to using national security as the justification. In the process, the U.S. economy is now more reliant on trade sanctions than its trading partners.

Investment Implications

One of the factors that contributed to the rally in U.S. and global equities this year was investor optimism that the U.S. and China would be able to achieve a truce in their conflict over trade. The failure to reach an agreement and the escalation in the dispute, therefore, has increased risks for the global economy and markets.

Thus far, equity markets have held up much better than late last year. The principal reasons are the world economy is in better shape today, and investors are still hopeful an agreement will be reached this year. However, we are less sanguine about the prospects for a trade deal anytime soon.

If so, the uncertainty over trade could undermine the improvement in the global economy and equity market volatility would likely rise from current levels. Meanwhile, we are maintaining our equity strategy that favors higher quality companies for what has proved to be an extended business cycle. At the same time, we are monitoring the global economy for signs of a renewed slowdown, which in our view, is the main risk today.

Thus far, equity markets have held up much better than late last year. The principal reasons are the world economy is in better shape today, and investors are still hopeful an agreement will be reached this year. However, we are less sanguine about the prospects for a trade deal anytime soon.

If so, the uncertainty over trade could undermine the improvement in the global economy and equity market volatility would likely rise from current levels. Meanwhile, we are maintaining our equity strategy that favors higher quality companies for what has proved to be an extended business cycle. At the same time, we are monitoring the global economy for signs of a renewed slowdown, which in our view, is the main risk today.

1“Trump’s Tariffs, Once Seen as Leverage, May Be Here to Stay,” May 14, 2019.