Despite this, the Federal Reserve raised the federal funds rate to a 22-year high of 5.5 % at the July FOMC meeting, and it left the door open to added tightening. The main reason: The Fed is worried that the tight U.S. labor market could keep wage pressures elevated and hinder its efforts to get inflation back to 2%.

Equity Investors Unfazed as Fed Raises Rates to 22-Year High

Nonetheless, equity investors appear unfazed by the Fed’s actions. The S&P 500 index has returned 20% so far this year, while the NASDAQ index is up by nearly 38%. In the process, these markets have recouped most of last year’s sell-off.

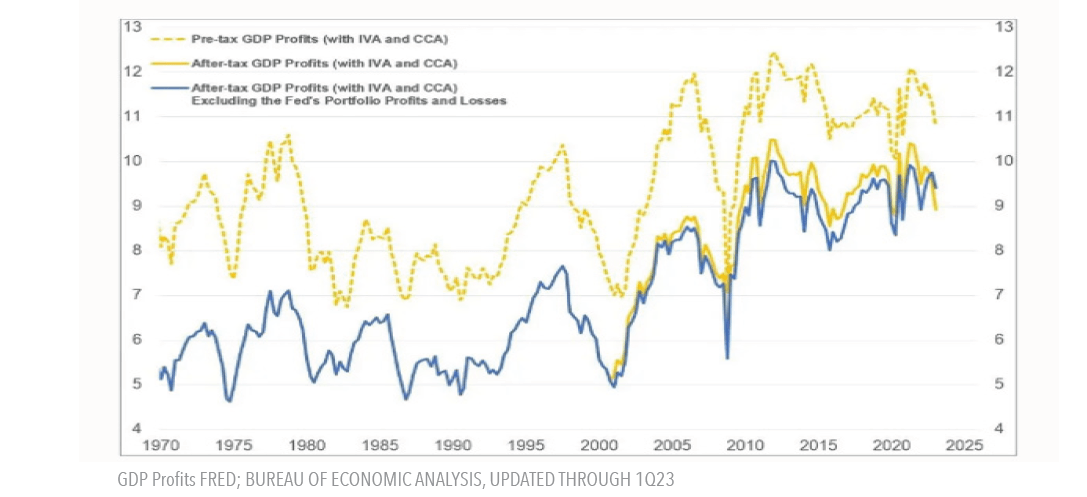

After-tax Profits for U.S. Businesses Remain High

Amid this, one issue that has received little attention is: Why have U.S. corporate profit margins remained high despite rising interest rates, wage increases and a strong dollar in 2022?

While some observers are wary that this anomaly will continue, Jim Glassman presents a more benign interpretation based on an analysis of Gross Domestic Income (GDI), which is the flip side of the GDP accounts1. He first points out that even with the economic slowdown last year, after-tax profits for all U.S. businesses have stayed near 10% of GDI, which is well above the average of 6% during the second half of the 20th century (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Profits of all U.S. Businesses Relative to Gross Domestic Income (%)

Emerging Economies Are Becoming Important Revenue Source

Glassman attributes the secular rise in the share of profits since the 1990s to offshoots from the Digital Revolution, including e-commerce, as well as financial deregulation that began in the 1980s. Globalization also contributed to the rise in U.S. profit margins as multinational corporations have earned substantial profits from overseas operations. In Glassman’s view, this implies that the appropriate yardstick for the stock market should be broader than U.S. GDP, especially as emerging economies become a more important source of revenue for U.S. businesses.

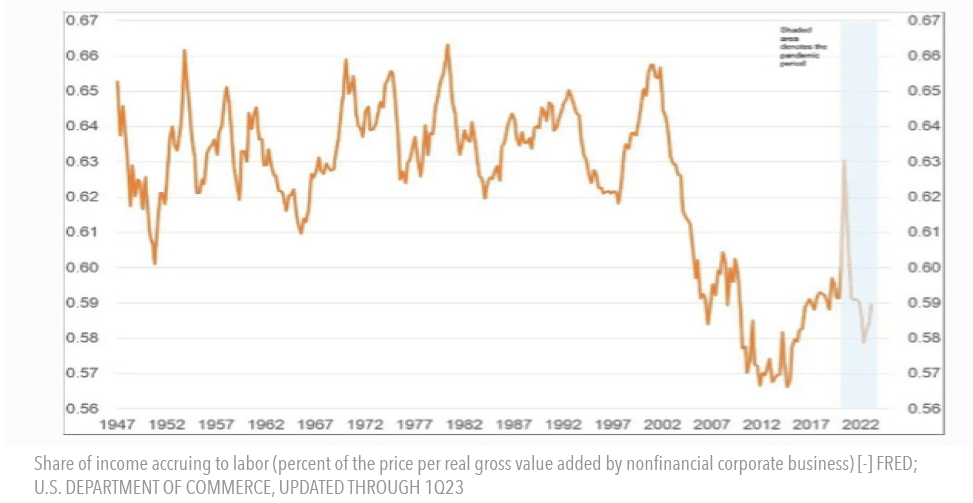

Labor's Share of National Income Has Declined

U.S. corporations are maintaining high-profit margins, even though the U.S. unemployment rate is at a record low: Labor’s share of national income currently is under 60%, well below the post-war average of 64% (Figure 2). This development is attributed to a significant change in the economy’s structure from a highly regulated one in the first half of the 20th century to a more open and competitive one in recent decades amid globalization. The share of the labor force that is unionized has also declined steadily since the 1980s, deducing its bargaining power.

Figure 2. Labor's Share of National Income

In Glassman’s view, these considerations lessen the risk that a tight labor market will fuel inflation: “The pricing dynamic turns upside down in competitive markets because, if businesses are not shielded from competition, they will be more disciplined about managing costs… In this case, prices would be expected to drive labor costs rather than the other way around, regardless of the strength of the labor markets.” It is only recently that wage increases have matched or exceeded inflation.

This interpretation is consistent with the findings of an NBER working paper on the topic. The paper found that if globalization or technological changes advantage the most productive firms in each industry, product market concentration will rise as industries become increasingly dominated by superstar firms with high profits and a low share of labor in firm value added and sales. “As the importance of superstar firms increases, the aggregate labor share will fall.”

Philips Curve Less Effective in Predicting Inflation

The assessments of Glassman and the NBER study help to shed light on why the Phillips curve – which depicts an inverse relation between the level of unemployment and the rate of inflation – has been less effective in predicting inflation for some time now. Yet, the Fed’s macroeconomic model incorporates elements of it, and it permeates the Fed’s thinking on inflation.

Will it Take a Recession for Inflation to Ease?

The main debate today among policymakers and investors is whether wage inflation will ease sufficiently to get inflation down to the Fed’s inflation target if economic growth continues at a moderate pace, or whether it will take a recession to get there.

On this score, recent economic data have been encouraging. For example, the employment cost index, a broad measure of labor costs that adjusts for shifts in the composition of the workforce, rose by 1.0% in the second quarter over the previous quarter. While the 4% annual rate is above what would be consistent with 2% inflation, it has decelerated from nearly a 5% pace in 2022. Moreover, wage and salary growth has slowed to an annual rate of 3.9%, the slowest pace since the second quarter of 2021.

Mickey Levy of Berenberg Securities points out, however, that wage increases for civilian workers, excluding incentive-paid occupations, remain elevated at nearly 4.8% over a year ago.2 He sees employment costs in certain sectors – notably healthcare and education – continuing to exert upward pressures on services inflation over the medium term. Accordingly, he expects inflation will stay above the Fed’s target through the end of next year.

Still, as inflation pressures ebb, the likelihood is that the Fed is nearing the end of its tightening cycle, and it could ease rates next year if the economy were to soften. In that event, the stock market could surrender some of its recent gains, but the market is unlikely to retest its previous low if corporate profits stay elevated.

1Jim Glassman, “The Economy’s Income Side,” July 27, 2023.

2Mickey Levy, “Real consumption turns up while PCE inflation decelerates in June,” U.S. Economic Brief, July 28, 2023.

A version of this article was posted to Forbes.com on August 1, 2023.