- Rather than unemployment rising because workers were laid off, which is the case when steep recessions occur, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a simultaneous reduction in the supply of workers as reflected in a decline in the labor force participation rate.

- With economic activity back close to its pre-pandemic level, the federal government is allowing the relief programs to expire, and it is likely that more people will return to the labor force as they draw down savings and as the pandemic is brought under control. Although, some people may opt to retire early or stay out of the labor force altogether.

- The challenge the Fed now faces in these circumstances is knowing when full employment has been attained to determine monetary policy

One of the key issues U.S. policymakers and investors confront is assessing how far the U.S. economy is from full employment. It has become the most important consideration in setting monetary policy since the Fed changed its operating procedures one year ago to target a 2% average annual rate of inflation and to permit temporary overshoots.

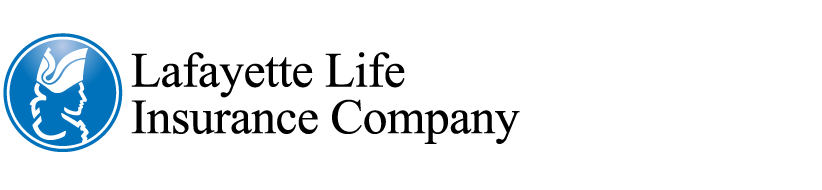

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in early 2020, the extent of job losses was much greater and happened more quickly than prior shocks. The main reason is that businesses and schools were closed to mitigate the spread of the pandemic. In April of 2020, the official unemployment rate stood at a post-war record of 15%, while a second measure of “underemployment” that includes people working part-time for economic reasons or marginally attached to the labor market approached 23%.

In the meantime, as businesses and schools have reopened, the unemployment rate has fallen steadily and currently stands at 5.2% (Figure 1). Sixteen million jobs, or three quarters of the more than 21 million lost during February-April of 2020, have been recovered. This leaves about 5 million jobs that have not recovered. The majority of them are in leisure and hospitality (1.6 million), government (0.7 million), admin and support (0.6 million), and healthcare (0.5 million).

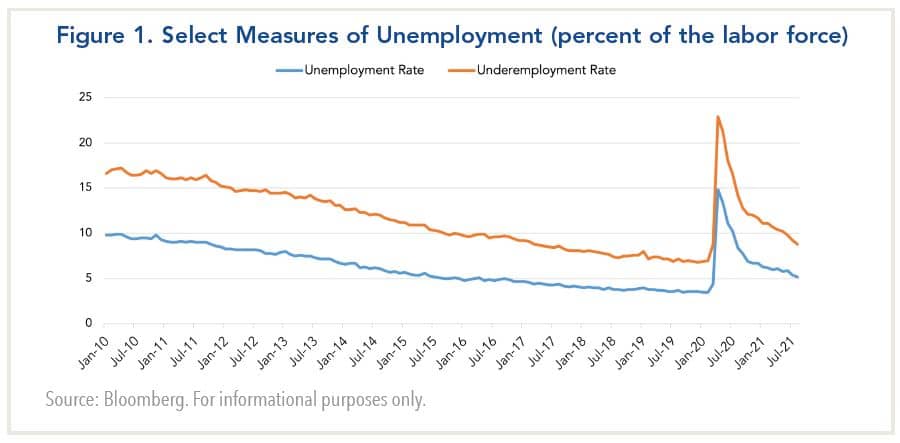

In setting monetary policy, the Fed now looks at a broader range of metrics relating to jobs rather than focus on the unemployment rate. For example, it is cognizant that the labor force participation rate is 1.8% below its pre-pandemic highs. Similarly, the ratio of people employed to the U.S. population is more than 2% below pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2).

In setting monetary policy, the Fed now looks at a broader range of metrics relating to jobs rather than focus on the unemployment rate. For example, it is cognizant that the labor force participation rate is 1.8% below its pre-pandemic highs. Similarly, the ratio of people employed to the U.S. population is more than 2% below pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2).

If you assume that the participation rate returns to prior levels and the labor force experienced natural growth throughout the pandemic, the potential number of jobs that could be created before reaching “full employment” is millions more than the number of jobs lost since early 2020.

However, several pandemic specific factors suggest these assumptions may overestimate the pool of available labor, including: 1) higher than normal retirements 2) increased number of people serving as caregivers, and 3) reduced immigration.

Consequently, using pre-pandemic levels of jobs and measures of unemployment may not be most useful to judge the progress of the labor market towards full employment. Even factoring in these uncertainties, the Fed does not believe the U.S economy is yet to its full potential, which is the main reason it is willing to keep interest rates close to zero for a while longer.

How Tight is the Labor Market?

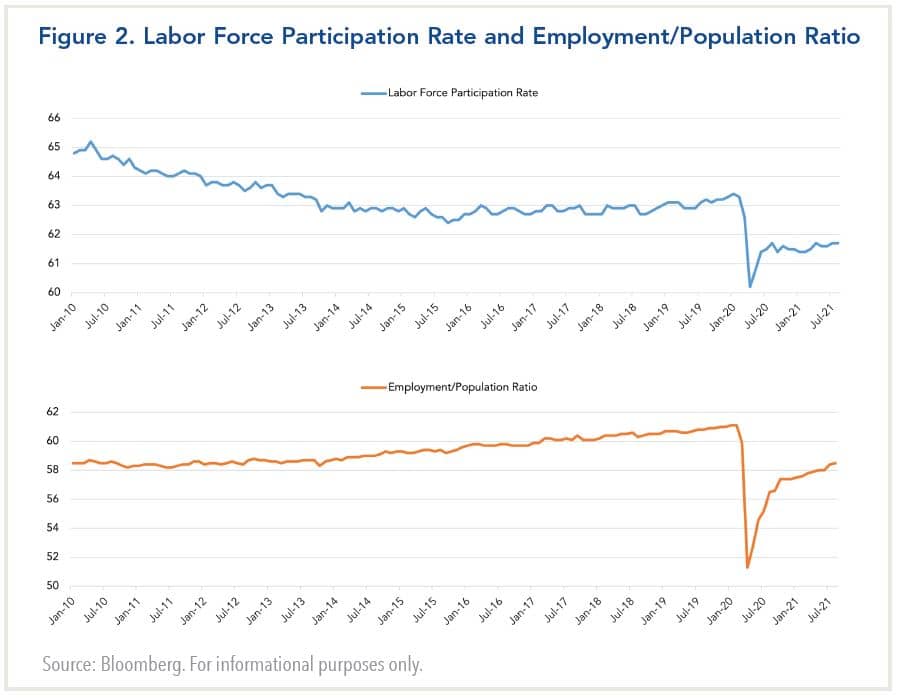

This assessment is confirmed in the Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for July (Figure 3). The report highlighted strength in labor demand, as job openings jumped to a record high of 10.9 million. It also pointed to ongoing labor supply shortages as reflected by a slowing in hires to 6.7 million and a surge in the quit rate of workers in the private sector. The 4.3 million gap between openings and hires is a record imbalance between labor demand and supply.

A widely held view is that workers who were laid off during the business shutdowns were able to reassess their long-term goals while they were supported by unemployment benefits that were both elevated and extended. Some observers contend that as these benefits are no longer being provided by the federal government and some state governments, unemployed workers will begin accepting positions that are available. With most pandemic-related benefits expiring in early September, the impact on labor supply may become clearer over the next few months.

What is clear is the JOLTS report and latest data on unemployment claims paint a picture of a strong labor market recovery. The slowdown in August nonfarm payrolls is widely attributed to the spread of the Delta variant, as indicated by slower growth of payrolls by businesses in the establishment survey. However, the household survey suggests stronger hiring of gig workers.

Meanwhile, the big unknown is the magnitude and impact the Delta variant will have on economic activity and demand for labor. The prevailing view is that it may reduce spending in high-contact sectors (travel, leisure, restaurants, etc.) and cause some businesses to delay the date that workers need to return to offices, but the impact is likely to be temporary.

Will the Labor Market Contribute to Higher Inflation?

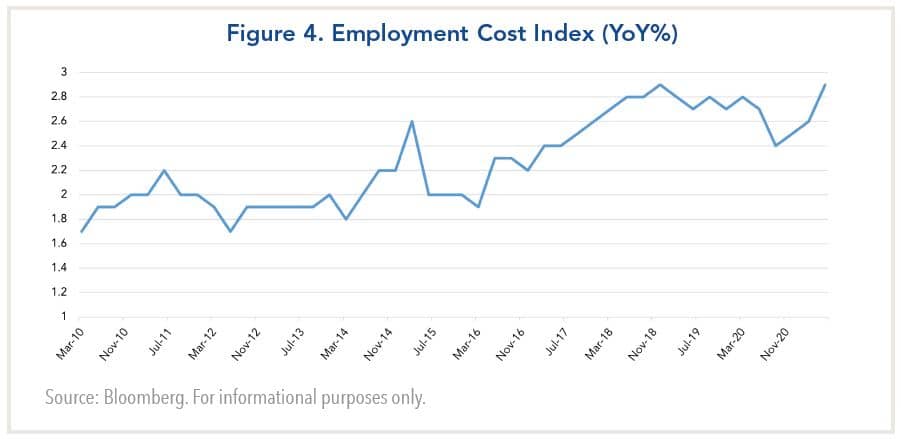

The extent of labor market tightness has important implications for the U.S. inflation outlook considering that wages are the biggest cost item for most businesses. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, it initially resulted in a slowing of wage increases. More recently, as the labor market has strengthened, wage increases have firmed, although the employment cost index is just back to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 4).

Not surprisingly, the industries that have experienced the largest wage increases are ones that were hardest hit by the pandemic and where workers are hesitant to return to their former jobs. There are also reports some businesses are offering signing bonuses to attract workers, but they are expected to be one-time payments.

From the Fed’s perspective, wage increases have been moderate overall and they are not likely to result in higher inflation, which it views as temporary. However, in the last six months inflation has been accelerating, and should it become embedded in peoples’ expectations, wages could accelerate at some point.

How the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed the Jobs Market and Fed Policy

The bottom line is the COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed how the U.S. labor market functions and Fed policy operates. Normally, when steep recessions occur unemployment rises because workers are laid off, and the Fed responds by lowering interest rates to boost demand.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, however, there was also a simultaneous reduction in the supply of workers as reflected in a decline in the labor force participation rate. This resulted from workers becoming concerned about their health and safety while also being supported by government programs that provided unemployment benefits that were both extended and elevated.

Today, with economic activity back close to its pre-pandemic level, the federal government is allowing the relief programs to expire. Consequently, it is likely that more people will return to the labor force as they draw down savings and as the pandemic is brought under control. However, some people may opt to retire early or stay out of the labor force because they are fatigued and/or do not believe the pay they might receive is worth their time and tribulations.

One challenge the Fed faces in these circumstances is knowing when full employment has been attained. Indeed, when there is a record gap of 4.3 million people between job openings and hires, how obligated should the Fed be to keep interest rates artificially low indefinitely?