- Fears of a U.S. recession have abated as investors anticipate a trade truce between the U.S. and China and policy easing by the Federal Reserve will bolster the economy next year.

- However, global growth remains soft and many economists are skeptical that actions by the Fed and other central banks will have much impact. The reasons: Interest rates are at record lows and monetary policies are not equipped to solve structural problems that plague economies today.

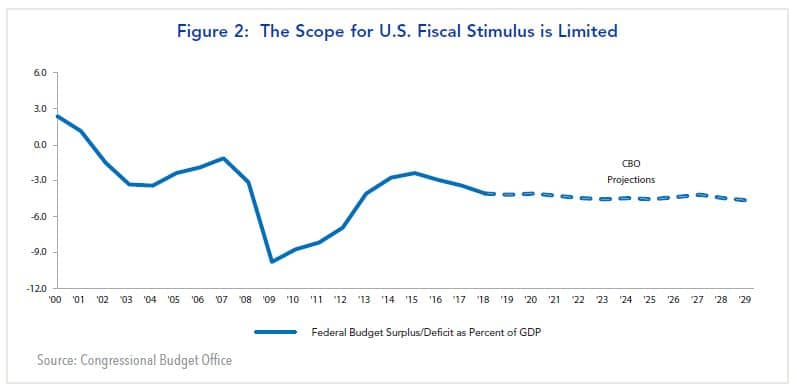

- This realization has led some to argue that fiscal policies should play a greater role. However, the prospects are limited, because the U.S. and many other countries are heavily indebted. Accordingly, lack of viable policy options is a risk investors need to consider should trade negotiations falter.

Recession Risks Lessen, but Slow Global Growth Persists

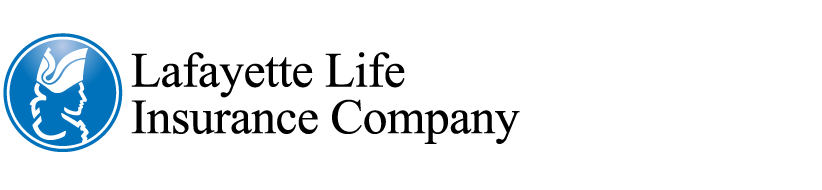

There has been a notable shift in investor sentiment in recent months, in which fears of a U.S. recession have given way to renewed hopes that the 10-year economic expansion will continue into 2020. This change is apparent in the U.S. Treasury yield curve’s shift from a mild inversion in August to being positively-sloped today (Figure 1). It is also reflected in the U.S. stock market’s steady climb to record highs.

The turn in sentiment primarily stems from two developments. One is that investors expect the U.S. and China will reach the first stage of a trade truce in which China agrees to purchase more agricultural products from the U.S. in exchange for a partial rollback of tariffs by the U.S. The second development is investors are hopeful that policy easing by the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of Japan, and China’s central bank will bolster global growth in 2020. Some observers believe that the Fed’s “mid-course correction,” in which the federal funds rate was lowered by 75 basis points this year, will produce a re-acceleration of growth similar to what happened in the second half of 2016.

Thus far, however, there is little to indicate that U.S. or global growth have begun to re-accelerate. The latest tracking of U.S. growth for the fourth quarter by the Atlanta Fed and the New York Fed place estimates at 0.3% to 0.4%, respectively, although final demand is expected to be stronger – in the vicinity of 1.5%. Growth in Europe continues to be soft, with the German economy stagnant and the U.K. economy facing uncertainty over Brexit.

Meanwhile, Chinese officials have conceded that it will be challenging for the economy to achieve the 6.0% growth threshold if the trade conflict with the U.S. persists. With recent press reports indicating an agreement on the first phase of the negotiations could be delayed until early next year, investors should consider what options policymakers have in the event global growth slows further.

Monetary Policy at the Zero Interest Rate Boundary

While investors seem confident that policy easing by central banks will be effective in countering global weakness, economists are much less sanguine. One of the themes at recent conferences I attended in Washington, D.C. and Vienna, Austria was that monetary policy has lost potency as interest rates have approached the zero boundary or turned negative throughout much of Europe and Japan.1

This problem first arose during the Great Depression, when bond yields plummeted toward very low levels in the 1930s in response to deflationary pressures. John Maynard Keynes described this situation as a “liquidity trap,” in which people hoard cash because they fear an adverse event such as a financial crisis, and changes in the money supply do not result in rising prices.2 More recently, Paul Krugman has updated the concept and depicts it as “a situation in which conventional monetary policies have become impotent, because nominal interest rates are at or near zero: injecting monetary base into the economy has no effect, because [monetary] base and bonds are viewed by the private sector as perfect substitutes.”3

In today’s context, many economists believe rates are unusually low because neutral rates that are consistent with full employment have fallen due to structural factors such as low productivity growth and demographics. In this environment, the transmission channels for monetary policy play out mainly through capital markets and exchange rates, rather than through banks, which desire to hold excess reserves.

The dilemma central banks face is depicted by Roberto Perli as one in which the power of monetary policy is diminishing.4 This is most evident in the inability of central banks to boost inflation to meet their stated targets despite massive policy easing. Perli concludes: “The best way for central banks to help the economy today is not to disappoint markets; all major central banks have adopted this point of view and they probably won’t abandon it anytime soon.”5

Role for Fiscal Policies Is Constrained

Faced with this dilemma, economists have looked at ways to coordinate monetary and fiscal policies to reach the objective of boosting growth. One proposal that has elicited some attention is by former Fed vice chairman Stanley Fisher (now with BlackRock) and others.6 It would have central banks create a facility to lend funds directly to the fiscal authorities, in which a central bank would independently decide when to activate such a facility and how much to lend. The fiscal authority would then decide how to spend the money. Central banks and fiscal authorities would also agree in advance on the conditions to stop the policy.

The advantage of this proposal is it would provide a way for the fiscal authorities to directly inject spending into the economy (via a form of “helicopter money”), but it would do so by setting boundaries on the amount of additional spending that is permitted. Some argue it is preferable to additional quantitative easing, in which central banks add to bank reserves in exchange for bonds, because banks typically hold the proceeds as excess reserves. They also maintain it is different from modern monetary theory (MMT) proposals, which imply potentially unlimited monetary financing of fiscal policies.

The main problem with implementing such a proposal now is the U.S. and many other governments already are highly indebted, and such an approach would add to the problem. The federal government’s budget deficit, for example, is now projected to range between 4%-5% of GDP for the foreseeable future (Figure 2), as aging demographics boost the cost of entitlement programs. The proposal also leaves open issues about how to ensure that central banks are not pressured to activate the borrowing facility and how to agree on an exit strategy.

In the current circumstances, many economists believe there is little room to expand the fiscal deficit. However, the conversation about implementing such a proposal could become more prominent when the next recession hits.

Weighing these considerations, investors should be cognizant of the risks that global economies face if a trade agreement is not reached or there is an unforeseen shock. As Roberto Perli observes:

“A few years ago, whoever would have dared propose anything like what we are talking about here would have gone to the equivalent of central banking jail – it was simply unthinkable to provide monetary financing to governments. The very fact that mainstream economists are willing to discuss policies like these shows how hard the problem we are facing is.”

1Conference sponsored by the Center for Financial Stability to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Bretton Woods, Washington, D.C., October 17, and 29th Annual

Roundtable sponsored by Austria’s Export Bank, OKB, Vienna Austria, November 11-12.

2The General Theory of Employment, Interest Rates and Money, 1936.

3“It’s Baaaack: Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, May 2013.

4“Why Monetary Policy Doesn’t Work Anymore,” Cornerstone Macro, October 17, 2019.

5Ibid, p.4.

6See Brian Chappatta, “BlackRock’s Ex-Central Bankers Have Bold Vision to Beat Recession,” Bloomberg Opinion, August 15, 2019.

7“How To Make Monetary Policy Work Again,” Cornerstone Macro, October 22, 2019.